A Clown FOR THE MACHINE: TONY OURSLER TAKES ON SURVEILLANCE

By Stephanie Berzon, May 3 2015

When Edward Snowden released classified information from the National Security Agency to mainstream media in 2013 he was globally marked as either a traitor or a patriot. The top-secret documents revealed that the NSA has been collecting data from anywhere and everywhere, including 55,000 quality images daily through social media and personal communications to use in facial recognition programs. The revelation confirmed civic anxieties that the dreaded future is here: your face can be used against you. However, as with all emerging sophisticated technologies, facial recognition sails in murky, unchartered waters; its full potential is unknown, as is solid legislation around it and its efficiency (a variety of photos of the Boston Marathon bombers were in the facial recognition database, but failed to matched to any identity). The computer application’s hidden omnipresence and its relationship with privacy and identity has inspired Tony Oursler’s new body of artwork at his fifth Lehmann Maupin solo show.

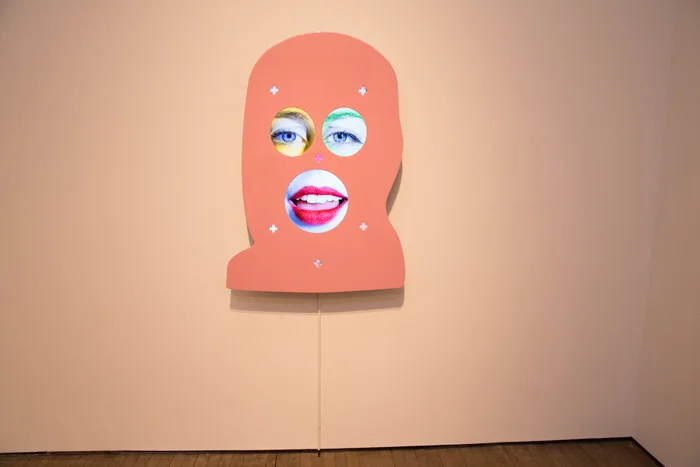

Installation view, photo: Frankie Galland

The exhibition features several large-scaled panel works of human faces, some coated with reflective or metallic surfaces, with various biometric maps spread across them that analyze certain areas of the face that remain unchanged over time. One freestanding piece highlights spatial relationships on the face with dotted lines, while another uses numbers to point out eye retinas and iris patterns. Computer algorithms are used to extract these features and match them to a person. Oursler, known for projecting his video work onto unlikely surfaces such as smoke, trees, or water, uses flat screens installed behind cut outs for eyes and mouths. However, his new work remains faithful to Ourslerian formality: shifty eyes and mouths whisper “now you’re a clown for the machine” or “I’ve been hacked all inside”—the dialogue of machines trying to process human emotions. Its conflation creates an existential void, anonymity with the art and ultimately a slight nauseating effect on the viewer.

Photos: Frankie Galland

It seems like a natural pursuit for the artist to be fascinated with new technologies that breach privacy and redefine what it means to be human. Oursler, a pioneer of new media art and expressionistic video theater, constantly pushes the limits of his craft and media, using human actors and dialogue to shape the concept. In 2004 he projected his own made-up face onto a meteor sculpture, the ultimate outsider, telling passersby at the Parrish Art Museum that “if you understand me, you understand yourself.” The multimedia Ourslerian process is to film the eyes and mouth separately, electronically stitch them with the script into one video and then project it on to a surface or screen it from behind (as in the Lehman Maupin show).

Photo: Frankie Galland

Oursler also points out that the social affairs and conflicts that happen in reality are mirrored in technology. There exists one black sculpture in the entire show, which raises the topic of racism in technology and the question of who is holding the mirror. At the opening reception of the show, the attendees were scanning and identifying the people around them as much as they were looking at the art, inadvertently participating in the very systems the body of art surrounding them discusses. In a gallery setting Oursler’s work inherently investigates how far the apple falls from the tree in a creator/product relationship and if technology is reflecting humans or if humans are beginning to reflect technology.