Art at the Edward Hopper House Art Center includes “Marion St. Burn,” a mixed-media piece by Tony Oursler.

As a mischievous boy in the late 1960s, Tony Oursler sneaked into Edward Hopper’s childhood home, then unoccupied and in disrepair, and just blocks from where Mr. Oursler’s family lived in Nyack, N.Y. Now an internationally recognized multimedia artist, Mr. Oursler has returned to the scene of his trespassing, today known as the Edward Hopper House Art Center, with “Tony Oursler: hopped (popped),” a site-specific installation that interweaves anecdotal snippets from his youth with biting reimaginings of Hopper’s complicated 43-year marriage.

Those reimaginings resulted from Mr. Oursler’s examination of a group of rarely exhibited caricatures that Hopper drew for his wife, Josephine Nivison Hopper, an artist herself as well as her husband’s model and muse. The introverted Hopper used the drawings to express his (often malevolent) sentiments about their relationship. Fifteen of the small pencil sketches, dating from 1933 to 1952, are on view in “Edward Hopper’s Caricatures: At Home With Ed and Jo,” in the Arthayer and Ruth Sanborn Gallery adjacent to “hopped (popped).”

The caricatures capture the couple’s marital strife, epitomized in “Chez Hopper — The Eternal Argument,” in which the two appear chest to chest as aggressive, squawking chickens. Some depict Jo haranguing Hopper. In “The Wedding Guest,” she sits in his lap, straddling his knees and grasping his jacket, a petite woman with a short ponytail. Mouth stretched wide, she spews at him, while he faces her passively, head hanging, eyes closed.

In other drawings, Hopper denigrates his wife as both painter and homemaker. She is portrayed with her dress blowing and her head poking through a torn canvas as she clutches her airborne easel in “Painting South Truro Church in the Wind”; in “Don’t Miss Anything Darling,” she squats between her husband’s legs and looks down, searching for specks of dirt.

“They’re about some kind of humorous yet tortured state the couple existed in,” Mr. Oursler, 55, said of the caricatures. “They’re quite tough, but they’re also hilarious.”

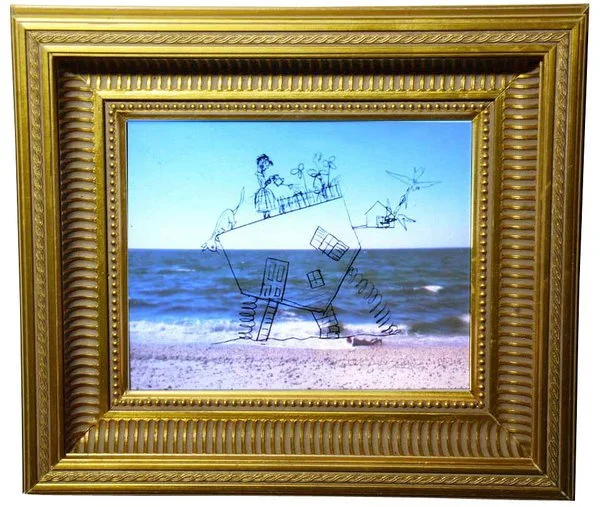

“The House That Jo Built,” by Edward Hopper.

EDWARD HOPPER, COURTESY OF THE ARTHAYER R. SANBORN HOPPER COLLECTION TRUST

Mr. Oursler brought toughness and hilarity into “hopped (popped),” along with a haunting sense of nostalgia. The installation consists of five individual pieces. It features multiple looping videos of re-enactments that characterize the Hoppers as represented in the caricatures and evoke Mr. Oursler’s memories of his suburban adolescence in the age of psychedelia.

The videos are projected onto mixed-media constructions — intricate assemblages of amateur-looking painted canvases, dollhouse-scale props and found objects. The piece titled “Marion St. Burn,” for example, consists of three paintings propped up on a platform. Crystals dangle from one canvas, which has a small, open door cut into it, and in front of the door, a curvy mirror suggests a liquid welcome mat. A doily hangs above a miniature upholstered chair that perches on a collapsed clay devil. All this serves as a three-dimensional “screen” for simultaneous projections. Orange light flickers like fire in the windows of a painted barn, rays of sunlight emerge from a cloudy sky, lacy abstractions filter through the doily. A woman with a pitchfork jabs at a man seated in the chair, who shoos her away yelling: “Out! Out!” In the center of the composition, two boys tread water, chanting phrases like, “Edward, come home,” “I’ve been on the porch all night long” and “I’m lost.”

Every element in these multifaceted pieces holds personal significance for Mr. Oursler. The canvases in the constructions were painted by students of his great-aunt, an artistic role model for him. “When she passed away, I took the paintings,” he said. “Using them was something special for me.”

A mixed-media work by Mr. Oursler.

To cast his videos, Mr. Oursler turned to family members. His father, bearing an uncanny resemblance to Hopper, is the man fending off the she-devil in “Marion St. Burn”; his son is one of the swimmers. In other pieces, his mother pontificates as Jo, his brother James clambers over a pile of rocks and Mr. Oursler himself crawls naked on a beach.

Incorporating his family was a first for the artist. “It made it more obviously true to my history,” he said.

Also true to his history are the locales in the videos. There’s the Hudson River, where Mr. Oursler, who now lives in Manhattan, used to swim. There’s Hook Mountain, where he caroused and which Hopper painted — “One of my favorite inspirational spots in the world,” Mr. Oursler said.

“The Wedding Guest,” by Edward Hopper.

EDWARD HOPPER, COURTESY OF THE ARTHAYER R. SANBORN HOPPER COLLECTION TRUST

ne of the projections was shot through the windshield of a car driving along Route 9W, a reference, Mr. Oursler explained, to the collision of the car culture and the drug culture of his teenage years. “There were a lot of casualties,” he said.

Noting the variations of scale in the works and the layered intermingling of script and image, Mr. Oursler described his installation as “kaleidoscopic” and “dreamlike.” Visitors in the darkened galleries are encouraged to come close to the pieces, to move around them, to listen and linger as the videos unfold.

Mr. Oursler is the second participant in a new program at Hopper House inviting contemporary artists to respond to the space. (The first was Christine Sciulli, who created a light installation in 2011.) In “hopped (popped),” he employs his signature projections to connect his life with Hopper’s. “I was thinking about the neighborhood where we both lived, and the differences between when he grew up and when I grew up,” he said, “and I began conflating the two in my mind.”