Bowie Collaborator Tony Oursler

on the Icon’s Art-World Ties, Generosity, and Final Years

By Boris Kachka

Published in Vulture Magazine, February 1, 2016

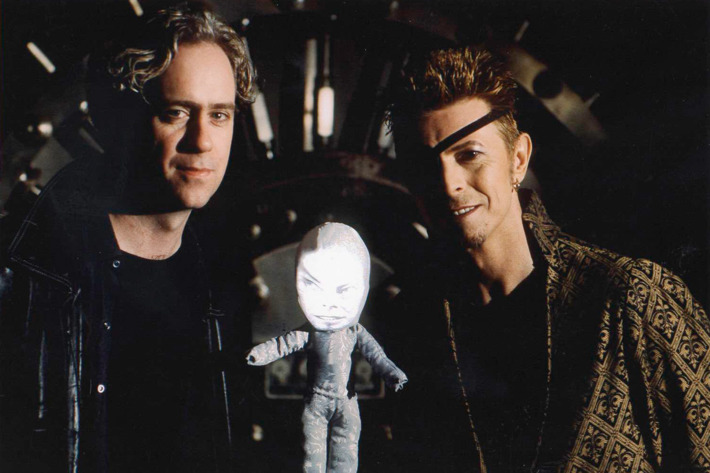

Oursler and Bowie. Photo: Linda Post

David Bowie was art’s hungry caterpillar, consuming everything in his path in order to transform himself aesthetically, again and again. Sometimes he drew the artists themselves into his orbit. One collaborator and friend was the prominent multimedia artist Tony Oursler. Within months of their meeting in 1996, Bowie was incorporating Oursler’s unsettling face projections into his Earthling tour and making cameos in the Oursler’s work. When Bowie made his 2013 comeback with the surprise release of The Next Day, Oursler directed the video of the first single, “Where Are We Now,” in which Bowie and Oursler’s wife appear in the artist’s studio as conjoined puppet heads. We spoke to Oursler last week in that studio, near the historic Henry Street Settlement on the far Lower East Side.

How did you and Bowie meet?

It was a funny circumstance. The curator Germano Celant was doing a sweeping group show [Florence’s “Time and Fashion”] with millions of great artists. I kind of hate fashion myself, and they always try to connect the two. But I looked at the list and saw David Bowie’s going to do an installation. So I thought, Wow, if David Bowie’s in it … So I sent my assistant [to set up the work]. She’s over in Italy, she calls me up and says, “You’ll never guess who I’m hanging out with. David really wants to meet you.” And I said, “Yeah, sure, I’m not gonna hold my breath.”

He really did. That show opened in September ’96; four months, later your designs were in his 50th birthday concert at Madison Square Garden.

Yeah, I got this phone call. I think I have it on tape somewhere. “Hello, David Bowie here.” I was just crying, playing it over and over again. I was living in this kind of hovel, a studio directly across from Max Fish. Classic old New York, rats coming through the ceiling. So he came over. It was the only place we could really meet.

Did he come just to see if he could use your work?

I think he just wanted to see how I was making things, how the effects were done. I think he liked to be around the creative process in general. I was really interested in how he composed his songs — I always wondered what his process was. But he didn’t like to talk about it that much.

He painted throughout his life, and your wife, Jacqueline Humphries, is an abstract painter. Did he ever ask what you thought of his visual art?

Nope. We talked a lot about art, but when you look at somebody like Bowie — he made all those rock videos, all those images, the music, the poetry, it’s the whole package. He was really a kind of new artistic figure, and I made it clear to him I thought that was the art. So the paintings are just one fragment of what the guy did and obviously not his most important part. I remember one really beautiful thing he said about composition. We were down at Jacqueline’s old studio, and she was doing a lot of scraping at the time. He said he really liked the way these patterns were revealed through scraping, and that it was very analogous to the way he composed music. He saw things as patterns that were overlaying one another. I said, “So you see the patterns in your head?” And he said, “Yes, I do.”

How did he ask to use your work?

What he wanted to do was take a series of my works and put them into his stage show. First I thought it was one or two things. Then I saw that it was a lot of different tropes, which was flattering and completely surprising. He was very respectful and said, “If it would affect your career in some way, I don’t want to do it.” I said, “Look, of course, but what would be great is if we could do a trade. You use some of these images onstage, and then you do something for one of my works.”

Sounds like a win-win. Did you help him set up those shows?

I shot the video with him for all the projections that we used, and I’m sure he could have shot it himself, but he just wanted it to look exactly how my shitty little camera made it look. But his team, once they saw how it worked in my studio, they were pretty slick about it. To prepare for the show at Madison Square Garden, he rented an arena in Connecticut that was the exact same size as MSG so that he could rehearse. I went up there to check it out with my sister, who had introduced me to Bowie’s music. We got to see a private showing in a giant, empty arena. That was spectacular, and also a testament to his perfectionism.

After his heart attack in 2004, he went quiet for a long time. You’ve said that you did see him in those years.

I did, but not a lot at first. I figured he was just sick. If I had a heart attack and vanished, it would probably be because I was sitting around thinking, I hope I’m alive, and reevaluating my life. He had one or two conversations with me about his health, about how he regrets smoking and it really fucked him up and diminished his lung capacity.

Did you ask if he was working on music?

I used to gently ask him about that. I’m kind of a workaholic myself, and I always admired that about him, that he was so driven. But he would say, “You’ll be the first to know.”

So what did you talk about?

Books, movies, paintings, installations, whatever. He read voraciously. During those ten years he told me that he read a book a day, and I believe it. He kept all his books in a row. He finished it, put it on the shelf. Instead of asking about what he was doing musically, I’d ask him what he was reading.

He liked to say in those years that he could navigate New York unrecognized. Was that true?

He had this one hat, and he could get away with it. But he seemed frustrated that he couldn’t just walk around. When we went to see the Whitney Biennial a couple of years back, we were spotted going in and the word spread like wildfire. There was a woman living in one of the galleries [as an installation], and she had music playing. Right before we came into the space, she put on one of his songs. It was kind of electric. But once we went to a Jasper Johns show at the MoMA, and it was like a circus. A group of middle-aged women came up and started touching him, grabbing at his shoulders and his back. That was the only time I saw him get a little bit uncomfortable. “Please stop touching me,” that was all he said. “Please stop touching me.”

He denied any official connection to the Victoria & Albert Museum’s “David Bowie Is” retrospective in 2013, which is still touring the world. What do you know about it?

Well, I sat with him and looked at the material.

In his house?

No, in his office. I never was in his house. We kicked around a lot of ideas about presentation. At a certain point I said, “Maybe for each phase you could invite a different artist to design an installation.” He had a kind of strange reaction to that. He said he thought it would be egomaniacal. That was interestingly humble of him, because I would do that if I were him.

How shocked where you when he came to you in 2012 with a new album — and then asked you to direct a secret music video — eight years after we’d last heard from him?

Well, I had just had a dream that David Bowie called me up and said, “I’ve got a new album I want you to hear, and I’m coming over your house,” and he came over and played me the album, and I was thinking, This one sounds way too much like Scary Monsters, but that one sounds incredible. He was torn between his future and his past on this new album [in my dream]. And two weeks later he emails me: “What are you doing?” And soon he’s sitting here playing me his new album …

The Next Day, in which he was torn between his future and his past. You know, our science blog recently covered a study showing that Bowie stars frequently in people’s hallucinations.

He had some serious stalkers, I think. After John Lennon was shot, he got very serious about that. He never talked about where he was going, ever. Just, “Gotta go.”

Did you know he was sick the last couple of years?

No. I was out of touch with him then. I just had emails back and forth. He wanted help with some painting that he was doing, but it never happened. One wonderful thing was that I had this big project — this book that I published called Imponderable. Basically, it’s an archive of stuff I’ve been collecting as a hobby. There’s one section that has to do with these abstract photos that are connected to Kirlian photography and auras and magnetic representations. David had at one point showed me a collection of Kirlian photographs that he took in the ‘70s, so I asked him if I could have a few of them for this project, and he was kind enough to let me have two. In fact I still have to give him — I promised him I would trade him something …

Unfinished business, I guess.

It’s funny. I sent him the book and he never said a word about it, and I thought maybe he didn’t like it. But I think he was just busy and sick. It’s strange because he was one of these guys — he would vanish for long periods of time, I wouldn’t hear from him. So it has this strange feeling, it’s like — just one of those things, “He’s gone.” You know? Like it’s kind of a trick.