“Caricature” for President!

An interview with the American artist and video sculpture pioneer Tony Oursler

Strangely enough, when I met up with the American artist Tony Oursler (1957), who has recently opened an extensive exhibition entitled ”M*r>0r” at the Magasin III Museum of Contemporary Art in Stockholm, it was not his own creatures that we discussed most of all; it was Donald Trump instead. The conversation took place about a month and a half before the U.S. elections; as I write these lines, the result still remains unknown. Nevertheless, it seems that there is, indeed, a direct link between Donald Trump and this wonderful and magical show, although the exhibition features no mention or play on his name, his hair, or any of his pronouncements. So what is it all about, then?

First off, Tony Oursler is one of the pioneers of video sculpture, and an artist who has paid a lot of attention to the subject of mass fascination with electronic media, including television and video. His works are in the collections of New York’s MoMA, Paris’s Centre Pompidou, the Tate Liverpool, and Cologne’s Museum Ludwig, among other prestigious art-institutions. And some of his works are, of course, also in the collection of Stockholm’s Magasin III, including his “TV Studio”, which was first shown here back in 2002: seemingly, an ordinary enough 1990s television studio, equipped with all sorts of editing devices, control panels, and monitors flashing mysterious and ghostly images. It is with this work that Oursler started the press tour for his latest exhibition as well. And it really is the heart of this whole “virtuality” and “surreality” business. Boxes of electronics, generating and transmitting images. Emitters of the matrix.

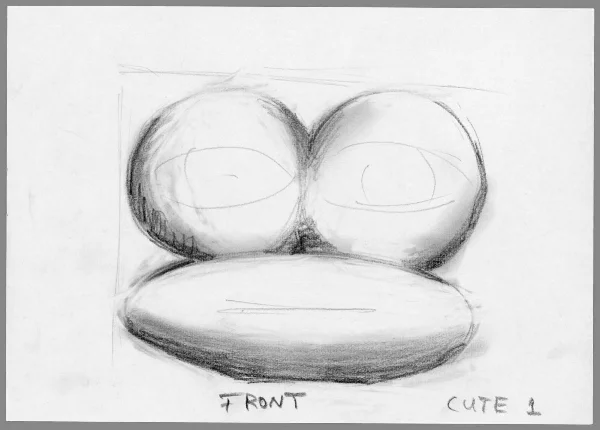

Sketch for “Caricature” by Tony Oursler, 2002Sketch for “Caricature” by Tony Oursler, 2002.

What is it that they are emitting, then? Tony made an attempt to define an answer to this question back in 2002 by creating his canonical “Caricature” ‒ the progenitor of a whole series of similar pieces. It is, essentially, a sort of living creature ‒ a giant smile with huge eyes, a nose-less, brainless and trunk-less hybrid, cheerfully mumbling away in child-speak. And, to tell the truth, no photograph I have ever seen has been able to do justice to the sensation you experience when standing right next to “Caricature”. It is an absolutely real and totally positive being that remains, at the same time, a complete fiction – a layering of video projections, a well of emptiness, a muezzin of nothing. And if muezzins call their listeners to prayers, what seems to be on offer here is a potential opportunity to “chill out”, “have fun”, “do some channel-surfing”.

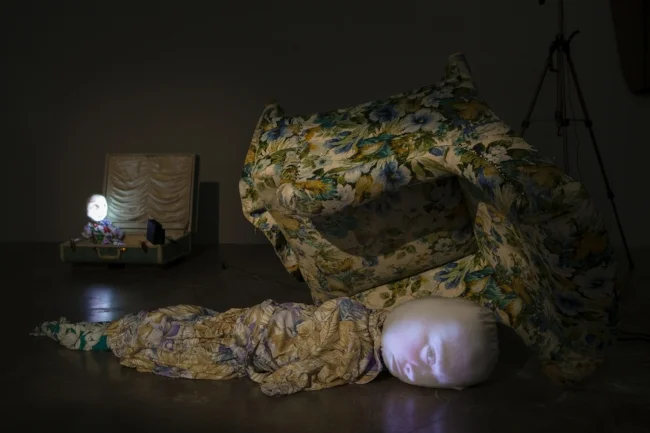

“Caricature” – it is also the next logical step following a whole “waxworks” of video sculptures to which Tony dedicated most of the 1990s. In his art practice, Oursler has been known to project video images on puffy rag dolls, balls, architectural structures, tree crowns, and even clouds of smoke, increasingly departing from classic homogeneous surfaces. (Even back in the 1980s, when the technical possibilities of projecting images on structures with volume were scarce, he did a lot of conjuring with images on the actual monitor, covering them in water or making them multiply with mirrors and broken glass...) A whole club of human-like video sculptures is also on view at the “M*r>0r” exhibition. They murmur, invite, accuse and appeal to the viewer’s feelings; they seduce. They never stop telling their story. Apart from a whole load of other references and codes, there is also a hinting at the kind of mystic cults that deal with making dead things come to life. Video voodoo.

Tony Oursler. Hard Case, 1995. Cloth figure, stuffed chair, video projection, performance by Tracey Leipold. Magasin III Production. Photo: Christian SaltaTony Oursler. Hard Case, 1995. Cloth figure, stuffed chair, video projection, performance by Tracey Leipold. Magasin III Production. Photo: Christian Saltas.

Incidentally, in one of his numerous interviews Tony Oursler spoke about “ridiculous cults” which, nevertheless, somehow manage to recruit new followers all the time ‒ about his urge to examine how these cults formed and how they were structured, because art, to an extent, worked in a very similar manner. According to Oursler, there exists a certain structure that helps you – if only for the briefest of moments, if only for a second – rise above the mundane, above reality, and look at the world from a completely different point of view.

And something very similar to this experience can definitely happen to you at Oursler’s Stockholm exhibition, which features an extremely impressive retrospective, but also premiers quite a number of completely new works. The latter deal with the subject of faces, both real ones and the illusory kind ‒ a subject that Tony finds very significant. According to another interview published a couple of years ago, Oursler has spent a lot of time studying the notion of an illusory face and looking for an answer as to what exactly can become a face: after all, we can recognize something very similar to facial features in any ornamental pattern. Lately, he has been focusing on the mechanism of computerized facial recognition based on the algorithm of the arrangement of nodal points and the distances between them. These kinds of algorithms are employed by a great variety of authorities and monitoring agencies; meanwhile, Tony Oursler uses them to create his art. It is quite typical of him: in a sense, it means taking back control, and recognizing ourselves in everything that surrounds us right now.

His works directly deal with our global reality, sometimes, quite spookily, predicting the next step in the development of a situation. For instance, I believe that his 1990s video sculptures anticipated the emergence of Donald Trump; as for “Caricature”, I see it as a representative of some future civilization. An outlandish, exaggerated 23rd-century entertainer.

Tony Oursler. Publicity photo

You know, I will definitely mention it in the introduction that a photograph does not deliver even a hundredth of the impact of seeing “Caricature” in real life. It is so incredibly “real” ‒ and also makes you think of a greeting from the future ‒ even from the distance of a couple of centuries or so. It’s like a stylization from the 23rd century...

[Chuckles] Yeah, that’s cool. I like the way that you mention that it’s from the future. I thought of it as these kind of futuristic characters that don’t have to eat, or breathe, or have certain body parts... that they’ve evolved on into a fantastic extension of our fantasy... a new from of engineered life.

But they communicate.

Yeah, they communicate very specific desires, a niche that they would fill in different people, and that would be their function. That piece really launched a group of works that I did for many years after that, five years or so. It opened up a whole morphology of characters that were quite humorous. They range from, like, very kid-friendly to sexual, monsters to toys. It was at the beginning of what you could do with aftereffects, which was a kind of video technology, it’s sort of like Photoshop for video – you can stretch things, morph things in different ways, that couldn’t really be done previous to that without millions of hours of rendering and so on. So I was able to kludge together these composites. I guess they have a kind of resonance with what’s happening now. We’re really on the cusp of that with CRISPR-Cas9 [the genome editing system]; we’re just this far away from going in and modifying everything. That, to me, is just the start of a new era of life forms... what’s going to happen with that – we just don’t know.

It’s like a revolution knocking at your door.

I’m not a futurist. I’m not one of those artists always talking about the future, that it’s going to be cool. But I kind of hate that about technology. Being a media artist, I would always get into these situations, like a colloquium on virtual reality, but in 1989 or 1990, where everyone’s so starry-eyed and saying “Oh, my God, it’s going to be so great”… The guy who developed the first headsets, the first thing he did was sell it to Atari for a first-person shooter game, and in the meantime, the guy is giving all these lectures on how wonderful it’s going to be, and he’s making all this money…

...from shooting games! [Both laugh]

Exactly… I’m much more interested in what’s going on now, like Pokemon Go!, and – what do they call it – augmented reality. I’m much more in the moment, generally, but I mean, fucking hell, man, CRISPR-Cas9 is like Pandora’s box. They’re trying to put these laws on it that will restrict how people do it, but it’s already been instantaneously [snaps fingers] broken by scientists, who have already done manipulations on humans. Plus, I think it’s easy to do; we’re going to see a time in which every tiny, little school is going to have the ability to modify genetics.

I can’t say I’m an expert in any way, but apparently, our DNA is old. There are still bits of you and me that they know are, like, a million years old, that go back to some sort of protozoa. I often feel protozoan when I wake up. We know that part of being human basically doesn’t change, but now, with the CRISPR-Cas9, if you do it in a certain way, it gets integrated into offspring. That means... that will be the first time that’s happened. That’s crazy and no one can oversee the technology. [Chuckles] It’s the end of one kind of human being, and the beginning of another.

I don’t know why people aren’t talking about it more. Because it’s very heavy, you know. And it’s probably happening right now, like there’s some guy, some rich dude in a lab trying to grow somebody with three heads or extra other body parts.

I think there’s a common feeling that we just can’t stop it.

You’re right about that.

Trashed, 1996. Cloth figures, wood, video projection, performance by Tracey Leipold. Photo: Courtesy of the artist

Today, at the press-review, I really liked your references to kabuki as one of the sources for inspiration for your video sculptures. When you sit and watch TV at home, you just watch, you just let it go. But if you change the angle slightly, you can see that it is actually kabuki… Something very formal and strange. Your video sculptures remind me of actors or TV-personalities with a removed background, with the superpower of the media removed… and we see that they are really kind of fragile and sentimental dolls.

I love that description; that they would become emotional skeletons via technological transmission. Sometimes I feel it's my job to capture a kind of poetry, and once it's recorded, it has a life of its own. Maybe that's what art is good at, but with pop culture, there’s“the willing suspension of disbelief” – we all agree that we’re going to have this illusion, we’re going to focus in, and go into that dream-space. The question is: What’s happening there? You mentioned before that things are out of control, and it starts with media; we move from the campfire to the camera obscura, to the magic lantern, to the phantasmagoria, to the film, to the television, to the computer, to the phone. And now, virtual headsets, which as much as I was dissing them, they’re going to be here in, like, a year or two. Every kid, like my kid, wants it because it’s the best.

The disjunction between reality and that world – why do we keep going there? Is it escape? A drug? Yes. I picked up a book by Jonathan Gottschall called “The Storytelling Animal” – he studies evolutionary narrative. He looks at things from the Charles Darwin point of view, but in terms of language and storytelling. I got this book and I was like “wow”, the guy’s fantastic. He doesn’t understand art at all... his education is like up to 1940 in terms of what a narrative is, which is unfortunate. But he’s got a great, great insight into narrative’s function. He did this great thing statistically, where he asked: What is narrative? It’s when we’re on the phone, when we’re talking, when we’re daydreaming – which turns out be almost a thousand times a day that we space out and daydream; when we’re dreaming; when we’re watching anything on screens; when we’re reading. You take that, and say – That’s the amount of time we spend in narrative? It’s massive. You have to add all that together, and it’s kind of fascinating for us, as cultural producers, to say that what we do is not on the outside – it’s reality.

It was interesting because in the beginning, you’re like, yeah, “the TV generation, computer-generated games – it’s a drug”. This guy comes along and puts it all together. It’s basically, kind of at the core of what it is to be human – to be in that dream space.

Tony Oursler’s “Talking Light” exhibition at the Lisson gallery, 1996.

But there are two sides to what is going on; we are increasingly more in this narrative field, but at the same time, these so-called real functions are becoming more and more formalized. You get the feeling that governments are also daydreaming, but at the same time, they move like these kabuki actors doing the traditional government-people movements.

That’s another story, which is that of the parent ritual. We have the government, the authority figure, the religious figure – they’re kind of all in the same category. And they’re more and more of a fantasy play, like you’re saying. They’re very symbolic, which they always have been. They’re very similar, formally, to kabuki. There we have Donald Trump, and there we have Hillary Clinton, two sides of the coin. And they know exactly what they’re doing. And their constituency fits perfectly into the fantasies that people have. They’re acting out these kinds of rites, which are basically meaningless except on a symbolic level because they won’t get anything done once they get elected. Generally.

To go back to a critique of capitalism – and I don’t say that lightly – when you have that kind of disenfranchised people, it seems that the story that they want is that of the scapegoat – somebody from another culture... someone came in and fucked up perfect America – when America was never perfect for everybody. And probably never will be. It’s like a project that’s always evolving…

But I think that the instant gratification part of media – it bypasses the notion of work. If you have people who want everything, but don’t have any connection to their labor, and hate what they do, it’s bad news. They want to have a millionaire’s lifestyle on a pauper’s salary. I think that’s part of what’s happening, and they’re never going to have that. Also, there's little sense of social responsibility in this form of capitalism. Donald Trump is the perfect example of a guy who basically cheated his way through a lot of his deals; he’s basically a con-man. It could be said that the Clintons are somewhat con-people also, but he’s hardcore. He doesn’t care about fucking other people over, along the way. Which maybe some people really like.

It’s strange.

People want someone tough. They think they’re not going to get cheated... they’re narcissistic. But to tell you the truth, I don’t understand it. I’m a little bit shocked by what’s going on… How do you take people who want to blame Mexico for their problems? That’s so fucking ridiculous – that Mexico is responsible for America’s problems.

It’s a “Caricature”.

It’s just unbelievable. The frightening thing is that you really understand fascism when half the population believes this kind of magical thinking. You start thinking about Germany in the ‘20s... it’s pretty hardcore.

Perhaps Hitler was the first video sculpture – he had these regular arm movements…

You know the guy was an artist, right?

Yes, he used to be a painter.

I didn’t understand that until maybe 20 years ago, when a friend of mine, Deborah Rothchild, did an exhibition titled “Hitler as Artist”. It had his notebooks, sketches for the uniforms, sketches for the pageants, all of which he designed. Popular legend has us believe that it was Speer, or Leni Riefenstahl, different people advising him. But it’s right in his fucking notebooks. He understood spectacle. He looked at opera quite a bit, and transposed it to the politics; that’s just what Trump does with his TV shows – he is now applying them to his politics. Look at Trump; there’s this amazing video of the Republican convention, when he came out with this light behind him. Let me show it to you... [looks for video on laptop] Here we go, you’re going to love this… [Queen’s “We Are the Champions” plays in the background as Trump enters the stage] Talk about a puppet.

It’s so much like video sculpture! At the same time he looks like a cheater, and he doesn’t try to hide it at all. To me, it kind of connects with the pieces in your exhibition because it has mostly faces – faces that are playing roles; you could say they’re simple, since they’re repeating, but they’re also very alive. You realize how everything is mechanical, but at the same time, alive.

I think you’re having an existential moment with that idea. Whereas someone like Obama, I think, is much more sophisticated... he knows the tricks, but he really is able to weave new messages in, new humanity, new ideas. But these guys... you’re right, it’s very robotic, it’s almost an automaton that takes statistical impulses. I think with the facial recognition piece, that’s something that I’m really interested in, the statistical aspect, what it is to be human, what it is to communicate. We’re on the cusp of these supercomputers that can analyze everything. Soon they’ll be analyzing sequences of gestures, sequences of language, and they’ll be like: that means this. They may know more about us than we do. It could almost be like interpreting the results of our interactions in real time, as they’re happening.

I think that the funny thing is, what if what it is to be human changes before we understand what it is to be human. That’s a kind of game; that’s what I realized with analyzing what it was like to grow up with television. I would read these books: “The TV Baby”, “The TV Generation”, etc., and they seemed not to understand anything about it, really. And by the time all these books were written, that generation was over [laughs]. Then the next trend starts, like video games, and I start to think, actually, we're never going to analyze these things in real time, or even after the fact. You’ve got to go to the gym metaphorically… like roll with it in real time. Because you have to shape it, not just react to it. Don't ask: What happened? Make it happen... No, you have to go make an app, make your own TV show, make your own art, and live it, instead of trying to analyze it, like, “what the fuck is Facebook going to mean to everybody?” [Both laugh] Well, I think that now people spend more than two hours a day, on average, doing Facebook. But by the time you have some real idea about what it meant, the next thing comes along. I think those days of long analysis are over.

Tony Oursler. ”1>mA”, 2016. Magasin III Production. Photo: Christian Saltas.

Going back to your video sculptures and faces. I can’t remember seeing an exhibition with so many faces, so many different expressions… Do you find faces interesting in general?

Here, the face becomes like a membrane for this information that’s aggregated. In other words, with the advent of this new facial recognition technology, it's the first time that a new kind of portrait emerges. The old idea of a portrait has to do with surface and light and likeness – any motion which is implied. But today, what we have is that imagery attached to all of our information – that could be our education, politics, economics, searches for preferences, basically anything that has been recorded, gathered and connected to us in real time. And as you probably know, the designs of these artworks are based on the algorithms used for facial recognition. These geometric forms are overlaid on the face, and then are matched up to the cardinal points of the face which, somehow, equal you and me. Of course, it’s not literally aggregated in the work, but it’s a kind of setting-up of the system into the work; the video stands in for almost a kind of life-force, or blood, or motivation… and the frame is this sort of schematic or template... the cookie cutter, the prison, the bondage... these works occupy the dichotomy we have been speaking about. Humanity and machine. What's interesting is that it is also self-created. Again, we made this technology for us, and we’re fully responsible for it. Once unleashed, what is going to happen with facial recognition? With this kind of aggregation? We are looking back at ourselves through the machine's Eye. It’s basically intelligent surveillance... Maybe there will be a way to activate you and me, but mostly, it’s going to be for the use of corporations and governments: I'm trying to activate you.

The key would be – How do we take that back? How’s that going to work for us? Maybe we can do that by understanding each other through this information.

Tony Oursler. Fap0s, 2016. Birch plywood, Sintra print, media players, sound and TV monitors. Magasin III Production. Photo: Christian Saltas.

I thought this was the best portrait exhibition I’ve seen in a long time. It made me think about what a contemporary portrait could actually look like. Especially the big works, in which some parts of the faces were unstable, and others were stationary. Because that’s what we’re really like – we are constantly moving a little bit, but some parts stay in place… When you work with “actors”, which you do quite a lot, do you know what sort of expression you want from them? Do you ask them to do something specific with their faces, or do you improvise?

I do a mixture. I’ll say: Make some faces. Usually, you have to push people a little bit, one way or another. I’m good at watching. I like to try and encourage the best performances. So it’s always a little bit collaborative because some people are just good at certain things, but have no ability with something else. I think I’m fairly good at recognizing that in real time, or teasing it out. Also, the way I shoot is strange because I’ll register people’s heads in a kind of bracket, so the camera can be close, and the head will be in a frame, and the lights are here, so it makes this weird cocoon for people. I’ve developed this method... it’s not really hypnosis, but it’s close to it.

“Watch as Tony takes you through his artistic process, from where he gets his ideas for the script, to videotaping his face, to the final art installation”

What was the first video sculpture that you made as an artist? What was the impulse behind making it three-dimensional?

You know, I started out as a painter, but I was never really satisfied with the painted image. I guess because being a “TV-baby” and "film freak", I was educated in sound and light... and also painting, because I really did study it. And if you think about history, at one point, painting was cinema or television... That was it. You look at Hieronymus Bosch – his things are completely cinematic. Every time I go to the Prado and see one of his paintings, it’s like a full science-fiction horror movie, mixed together with religious film…

So then I moved into video; I immediately picked up the camera and that [snaps fingers] was what was missing. I’m combining things, I’m making it in real time, looking at the monitor through the camera, composing images. But soon thereafter, I started to think – I want to get the power of the moving image, but I don’t want that frame: the corporate Sony or RCA, corporate 4:3 aspect ratio of the TV screen. Unlike Nam June [Paik] and other people who really celebrated that; they had their own way of messing with it – with magnets, or stacking them, or putting them into things. But for me, I just like the movement and the texture of it – the sheer electric virtuality. The projectors back then were impossible: shitty, super-expensive, you had to be in a completely dark room, etc., etc. Inaccessible to art, mostly. To make a long story short, I started to use lenses, glass, mirrors, things like that to kind of lift the image off the screen. I worked like that for many years – making installations with reflected images and glass, reflected in water...it was experimental stuff. I always think I'm making an experiment.

I guess the first pieces I made with that was around 1981 – “Son of Oil” was the name of the piece. Then I did my first immersive piece – that is when you walked into “L7-L5”, in 1984. I was using the monitors in sculpture, but you couldn't see the actual monitor or use many devices to remove the image. And then, it’s almost ten years later with the first small projectors. I really worked a long time with those other installations, with TVs. It felt like a total relief when I could project onto surfaces. If you look at the physics of light... all of the colors are absorbed except for the one that you see. So with projection, it’s an interruption in this primary physics of looking, and that, to me, is fascinating. That interruption was such a breakthrough for me, and it came at just the time when I really fell in love with those small projectors. That was in 1990 or ‘91, and that led to a kind of “getting outside of the box” – that’s what people said when they looked at my work.

Tony Oursler among his creatures at the Magasin III Museum of Contemporary Art, in Stockhol.

So, in a way, you were waiting for technology to get to this level?

I didn’t know, I had no idea. It was a strange point in my life because I had kind of given up on the art world as any kind of support. I couldn’t make any money, at all. People were not interested in the moving image. And I was really puzzled because certain artists had seemed to be successful: Nam June, Vito Acconci, Dara Birnbaum, Gretchen Bender, Wolf Vostell…

Now I have more perspective on it; everything goes in cycles. Video was super interesting to the art world probably in the early ‘70s, then it sort of went out of fashion, other things captured the imagination. But also at that time, there was a very conservative approach to media, and I fell into it. Me, being a TV-child / product of media, well, so was everyone else – they have two or three TVs in their house, they have radios, a telephone… So what’s the problem? Why won’t they allow that into the art space? It was very segregated: painting, photography (which had just started to become accepted at that time), sculpture... When you’re a kid, like 20 years old, you just see that it makes sense; what’s the big deal?

So I just said: Whatever, I’m going to keep going with my experiments. I got a teaching job in Boston... and I was like, whatever, fuck the art world – I’m just doing what I want to do. I started teaching installation at Massachusetts College of Art in Boston, and I had enough money to live. It was perfect: I can have my think-tank at the school, I had plenty of time to make my own work… what more can one ask for ?

And then these small video projectors came in, and [snaps fingers] it changed everything for me. It was also the year that Jan Hoet (who just died last year) curated dOCUMENTA 9, and I was very honored to be in that. In that year it was Matt Barney, Bill Viola, me, Mike Kelley, Cady Noland, Franz West... so it was kind of like installation and moving image at that point. It was great. I felt like that was a watermark... It was an important moment for me. But these things are cyclical.

Right now, I don’t think it’s happening – with the moving image. People are not interrogating it, and there’s not an interest in that. It’s another cyclical moment in which abstract painting is back, painting is back, and then painting is back, and then painting is back, and then there’s also more painting, and then there’s, again, more painting… It’s the moment of painting, obviously. It’s all over the world; but that’s OK, that’s the cycle. People will get interested in augmented reality, or virtual reality will be the next thing that people want to do… it’s all cyclical.

A peek into Tony Oursler’s studio. Assistant curator from Magasin III, Jen Lindblad filmed this video series when she visited the studio in summer 2016

And VR headset now is the next technical tool that could move art and the moving image to the next level?

Definitely. I just finished a virtual reality project. I recently got back into narrative; I had moved away from narrative (beginning, middle, and end) for years and years, for more of an abstract kind of poetry that would maybe activate the viewer in real time, keep it non-linear, in more of an installation. I explored that for ten, twenty years, with some narrative in-between, but after that I made “Imponderable”, with the Luma Foundation and my curator friends Tom Eccles and Beatrix Ruff; and then I made two more films, and then one of the films turned into a short virtual-reality project. We worked on converting this video into a very simple, but elegant, humorous VR-space. The technology is quite impressive; the guy who came to my studio, Peter Fischer, he put on a simple shooting game with laser beams. My son put on the goggles, and he just wouldn’t get off it (he’s twelve-and-a-half years old). My son, Jack, was so affected by it; he said: “Dad, that’s the best video game I’ve ever played”. And he plays all the video games, I’m sad to say. He’s an expert at all the murderous video games out there…

Film still from “Imponderable”, 2015.

Within a couple of years, we’re going to see a whole generation of people with all these VR-things on. Virtual reality is a bubble right now. I can imagine a transparent screen, so that you’re really in VR, but virtual, so you could have both. But there’s something about it – the fantasy – which is a little bit too much. It’s almost like eating a cake, but then you get to the frosting, which is just sugar.

What’s going to happen? Metaphorically, you can get sick and fall down. I was working with the designer Peter Fisher, and I said: How about we have all this moving? And he said we can’t do that because people actually get sick; they get dizzy, they can fall. You can seriously mess with the anatomical parts of the brain by doing that. You won’t get permanently sick, but you could fall and break your arm, or something.

It’s interesting to end our conversation with that, because we began with: Why do we want to go into that you get in there, and it’s a bit like kabuki, because it’s actually low-res. It doesn’t have to be 4K, no. It works with quite low resolution, and you’re completely convinced that something’s coming at you. But an interesting warning: the reason that we may feel nauseated anatomically when we use the VR system is that, through evolution, the brain evolved a sense of discrepancy between motion and balance. When that relationship is disrupted, it's often the result of toxicity, for example, being drunk – the brain’s evolutionary response is to get sick and remove the toxins. The question is: is VR poison? Anyway, artists are going to go crazy with it. They’re going to have a great time, I’m sure.