Fault Line

By John Yao

Postcard of manipulated photograph titled “Snow ghosts in the forest,” Switzerland, 1931 (all images courtesy Tony Oursler’s personal archive)

The first paragraph of Lev Manovich’s groundbreaking essay “Database as Symbolic Form” (1999) came to mind about three minutes after I began pouring over the weird, wacky, wild, and wooly stuff displayed under glass in Tony Oursler: The Imponderable Archive at the Hessel Museum of Art at the Bard Center of Curatorial Studies (June 24–October 30, 2016):

After the novel, and subsequently cinema, privileged narrative as the key form of cultural expression of the modern age, the computer age introduces its correlate – database. Many new media objects do not tell stories; they don’t have a beginning or end; in fact, they don’t have any development, thematically, formally or otherwise which would organize their elements into a sequence. Instead, they are collections of individual items, where every item has the same significance as any other.

Oursler’s archive of the occult can be seen as a database; it can also be a labyrinth, which, in this case, has at least two entrances. One entrance opens to the exhibit and the other leads us to its equally fascinating backstory.

A hypnotist entrances several young men onstage, mid-20th century

I will start with the latter. Tony Oursler’s full name is Charles Fulton Oursler III. His grandfather Fulton — which was how he was known — seems to have lived two distinct lives, as a disbeliever and a believer. These two sides — the skeptic and the supporter — seem to have twisted around each other like the snakes on Caduceus’ staff.

In the 1920s, after the countless deaths of World War I, Fulton was known for debunking spiritual mediums who claimed they could contact spirits in the afterlife. He was befriended by the magician Harry Houdini, a fellow debunker, and corresponded with the detective novelist Arthur Conan Doyle, a believer in fairies and spiritualists.

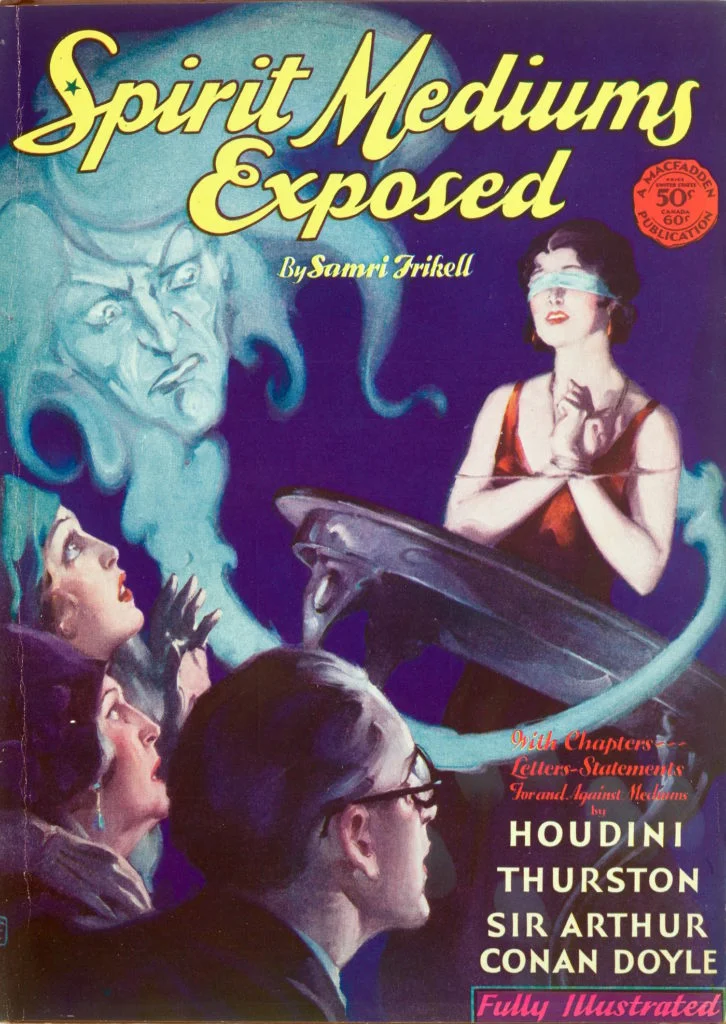

“Spirit Mediums Exposed” by Samri Frikell (one of the pen names of Fulton Oursler), published in 1930 by Macfadden Publications Inc.

During this period Fulton was a stage magician, a senior editor at the pulp magazines True Detectiveand True Romance, and wrote mysteries, detective fiction, and Hollywood screenplays (often under a pseudonym). Writing under the name Samri Frikell, he declared in his book Spirit Mediums Exposed (1930):

I am the foe of fakery, of charlatanism, of hoodwinkers, of wonder-mongers, of miracle pretenders — of BUNK. And of all the low-down creatures in the world, the religious faker, the scoundrel that pretends to trusting and ignorant people that he can bring them face to face and voice to voice with their beloved dead, is the most contemptible.

Fulton’s wife, the artist’s grandmother, was Grace Perkins, who also wrote genre fiction and screenplays, most notably the precode Night Nurse (1931), directed by William Wellman, and starring Barbara Stanwyck and Joan Blondell.

Later in his life, after he went to Alcoholics Anonymous, got dry and became a Roman Catholic, he wrote The Greatest Story Ever Told: A Tale of the Greatest Life Ever Lived (1949), which was turned into the movie The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), directed by George Stevens, with a cast that included Max von Sydow, Charlton Heston, and Telly Savalas — Jesus’ life as colorful Hollywood entertainment. Fulton’s son was the editor of the Christian magazine, Guideposts, as well as the founding editor of the magazine Angels on Earth, which purported to be about what the title suggests, the actual adventures of angels on earth. Although this shift from disbelief to belief is just part of the backstory, which continues through the artist’s father to the son, Tony Oursler, it helps explain the origin of this massive collection, which has been maintained and augmented over three generations.

Oursler’s archive is the mother lode of all things occult: it has everything for anyone who has ever expressed even a passing interest in UFOs, satanists, hippies, necromancy, séances, mermaids, voodoo, spirit photography, shrunken heads, Tibetan skulls, nudists, the mediumistic art of Madge Gill, the English Paracelsian and occultist Robert Fludd, Aleister Crowley, the dream drawings of Federico Fellini, tarot decks, fortune telling, alchemy, ghosts, horror movies, film stills, Kabbalah, and Big Foot. Believe me when I say this list is only a small part of what can be found in the books, magazines, posters, postcards, photographs, newspaper articles, drawings, masks, objects, diaries, and charts housed in the collection, with topics that run the gamut from scientists and experiments to magicians and sideshows, making every conceivable stop along the way.

I was fascinated, creeped-out, amused, disturbed, flabbergasted, and, most of all, overwhelmed by the sheer amount of things, nearly 700 in all, to look at. For every objective study I saw, there was a lurid counterpart. It seems that the entire collection is comprised of around 3,000 items. However, do not despair: the exhibition, which was curated by Tom Eccles and Beatrix Ruf, is accompanied by a beautifully designed telephone book of a catalogue full of illustrations and nearly a dozen essays. The images are “sequenced” by Oursler, and the first one we see is sepia-toned photograph of the Temple of Sibyl outside Rome. While I recognize that it was probably very difficult to do, I do wish the catalogue had an index.

While much of the emphasis of the essays is, understandably, on debunking, we live in crazy times. Here is what Louisiana State Senator John Milkovich said to fellow Louisiana State Senator Dan Claitor:

[…] are you aware that there is an abundance of recent science that actually confirms the Genesis account of creation?”

Creationism — which denies evolution — can still be taught in Louisiana public schools. In Kentucky, there is a theme park devoted to Noah’s Ark, complete with dinosaurs. However, before you start snickering, may I remind you that Madame Blavatsky, who wrote the influential The Secret Doctrine, had a stuffed baboon dressed in a suit in her study; in its hand was a copy of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species. Wassily Kandinsky, Frantisek Kupka, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimer Malevich read Blavatsky’s writings and believed they could evolve spiritually and reach a higher plane of consciousness. In the late 1870s, Hilma Af Klint, a pioneer of abstract art, attended a séance. She and four other women formed a group, “The Five” (de fem), that had séances, which, in Af Klint’s case, inspired her to begin a form of automatic drawing.

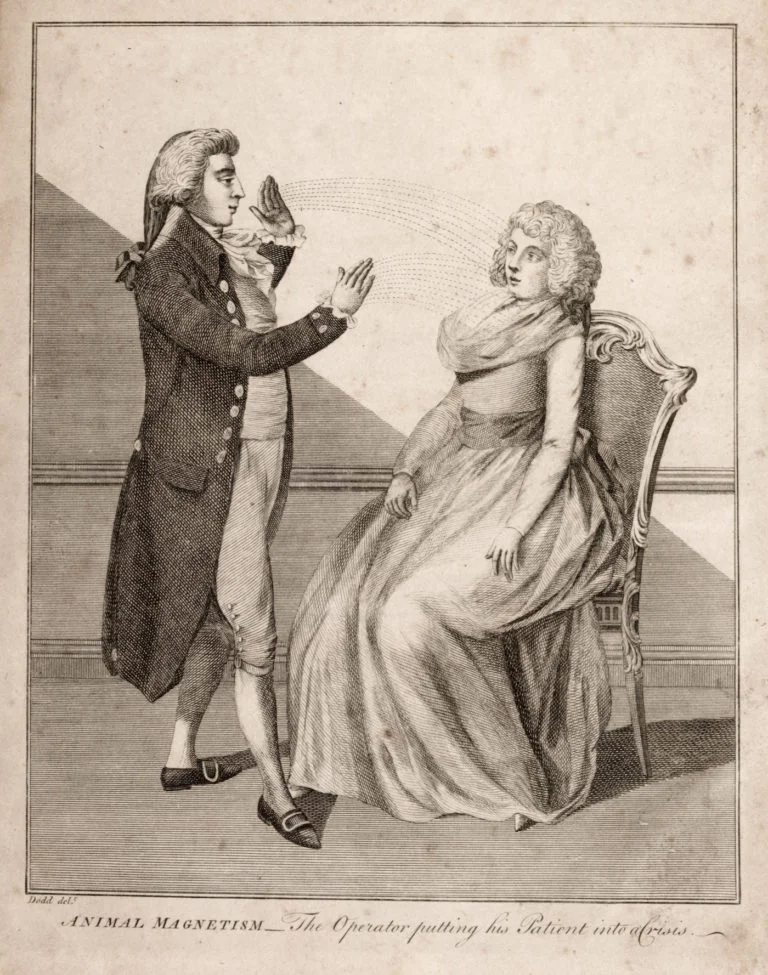

An illustration of Animal Magnetism, “The Operator putting his Patient into a Crisis,” from “A Key to Physic, and the Occult Sciences” by E. Sibly, 1810

In art there is a longstanding argument between the materialists and those who believe in immateriality. Where do you put Forrest Bess? His letters to Meyer Shapiro and others could easily be included in Oursler’s “archive,” as could the sessions that Budd Hopkins taped with UFO abductees. Known as the “father of the abduction movement,” Hopkins was a painter, sculptor and author of Missing Time: A Documented Study of Alien Abductions (1981) and Intruders: The Incredible Visitations at Copley Woods (1987). Does his work in the field of UFOs discredit his art? What about the work of Alfred Jensen, Jess, Harry Smith, or Bruce Conner? And let’s not forget Agnes Martin who — in the documentary film Agnes Martin: With My Back to the World(2002) — claimed to have been reincarnated more than once.

Oursler’s archive shows every side to all sorts of phenomena or what the catalogue calls the “Imponderable.” Ezra Pound said that myths began when a person saw something in the woods that could not be explained and tried to tell someone what happened. When I left the exhibition — which I highly recommend you go and see — I realized that I had not pondered all that I could. In fact, there are two video installations, “Le Volcan” and “My Saturnian Lover(s),” which I did not look at because they required a different kind of engagement. This is definitely a trip I will make again this summer, going from Manhattan to Bard.

Oursler’s “archive” sits squarely on a fault line running through modern art. On one side are those who insist that art is about materiality and visibility, while on the far shore there is another equally adamant group that insists on striving towards the invisible and immateriality. While I don’t think you need to take sides to be enthralled by what Oursler presents to us, I do think it is an argument that should be kept in mind. No matter when art was made — from the caves to studios to post-studios — the artist had a belief system. We are the beneficiaries of the art, even if we find the system questionable.

Tony Oursler: The Imponderable Archive continues at the Hessel Museum of Art at the Bard Center of Curatorial Studies (33 Garden Rd, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York) through October 30.