Kunstlerhaus Salzburg | Salzburger Kunstverein, Kenstlerhaus, Hellbrunner StraBe 3 | Salzburg, 5020 | Austria

Mar. 1 - Apr. 1, 1994

Multiple Personality Disorder, a pseudo-scientific term never accepted by the American Medical Association, is at the core of this installation. MPD has an important position in Oursler's oeuvre: he links its historical arc to popular culture, the mass media, psychosomatics and identity. Although the Bible referenced multiplicity and possessions -for example in Luke 8:34 when Christ casts numerous spirits out of men into a herd of pigs- the modern notion of more than one identity existing within a person has its origins in psychoanalysis with Pierre Janet (1859-1947) and his theory on duality (de?doublement). Multiplicity, always negatively valued and associated with trauma and diminishing of the self, continues to proliferate in the US in medical and pop cultural contexts. In 1957 the thinly veiled tale of liberation The Three Faces of Eve won an Oscar. By the late '80s, psychiatrists were beginning to use the terms "switching" and "channeling" when discussing MPD, and patients claiming to possess as many as a hundred personalities now regularly appear on talk shows.

The growth of this phenomenon parallels the development of home multimedia, the women's liberation movement, and the internet. In a famed 1997 lawsuit against psychiatrist Dr. Bennett Braun, in which a patient was falsely convinced through hypnosis that she had committed hundreds of murders in satanic rituals, the process was proven to actually provoke and trigger multiple personalities within the patient and the entire phenomenon collapsed. Although MPD is often associated with victim culture, Oursler is attracted to the feminist perspective of MPD, which saw the phenomenon as a break with the patriarchal archetypes of Freud and opened new territory for malleable or flexible identity formation evidenced by the internet. The artist studied the method of hypnotic abreaction practiced by many therapists and used to communicate with those affected by 'multiple' syndrome. Many of the scripts written in this period are derived from those transcripts.

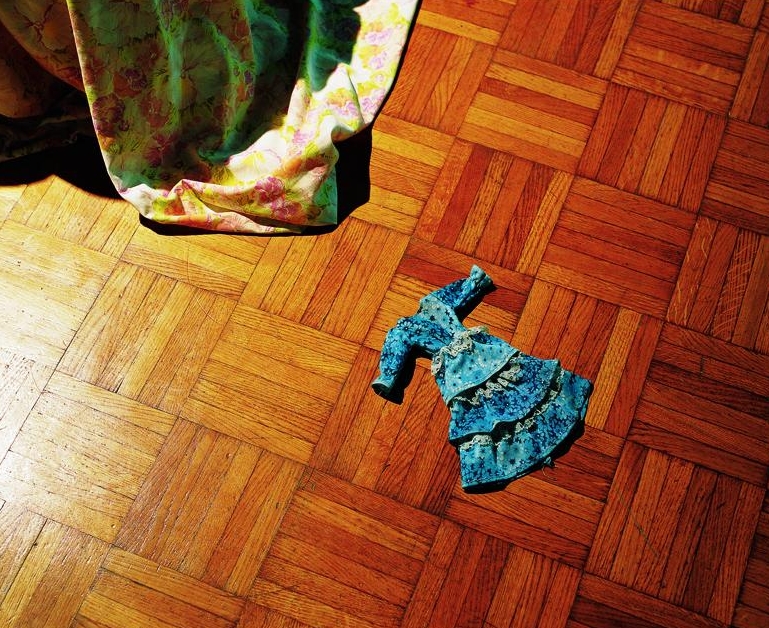

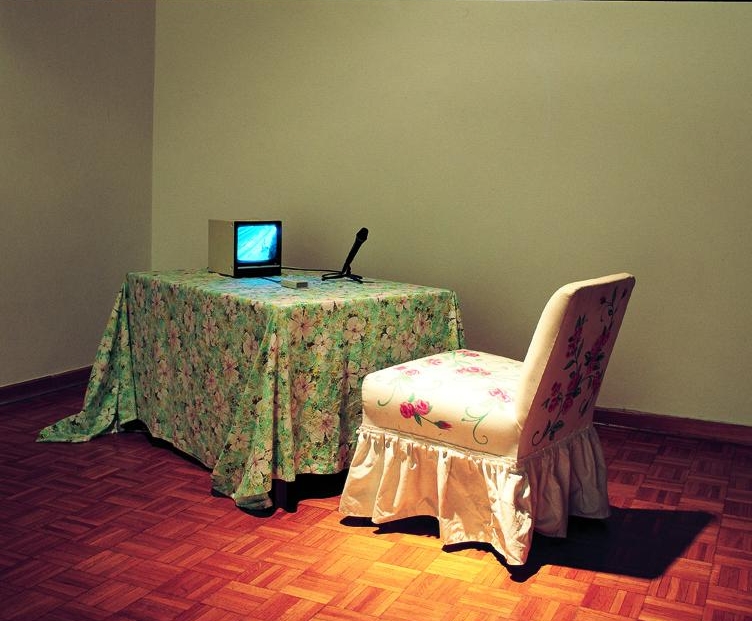

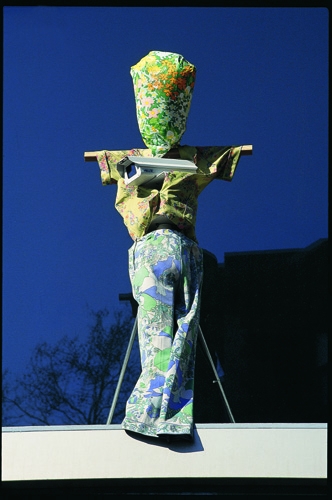

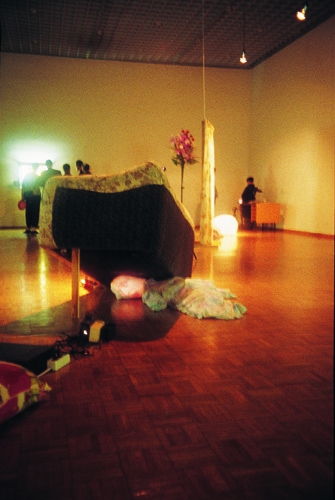

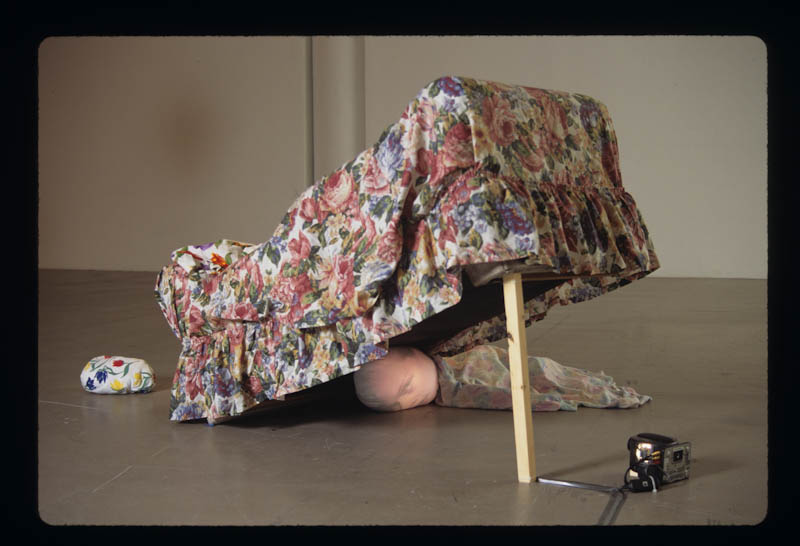

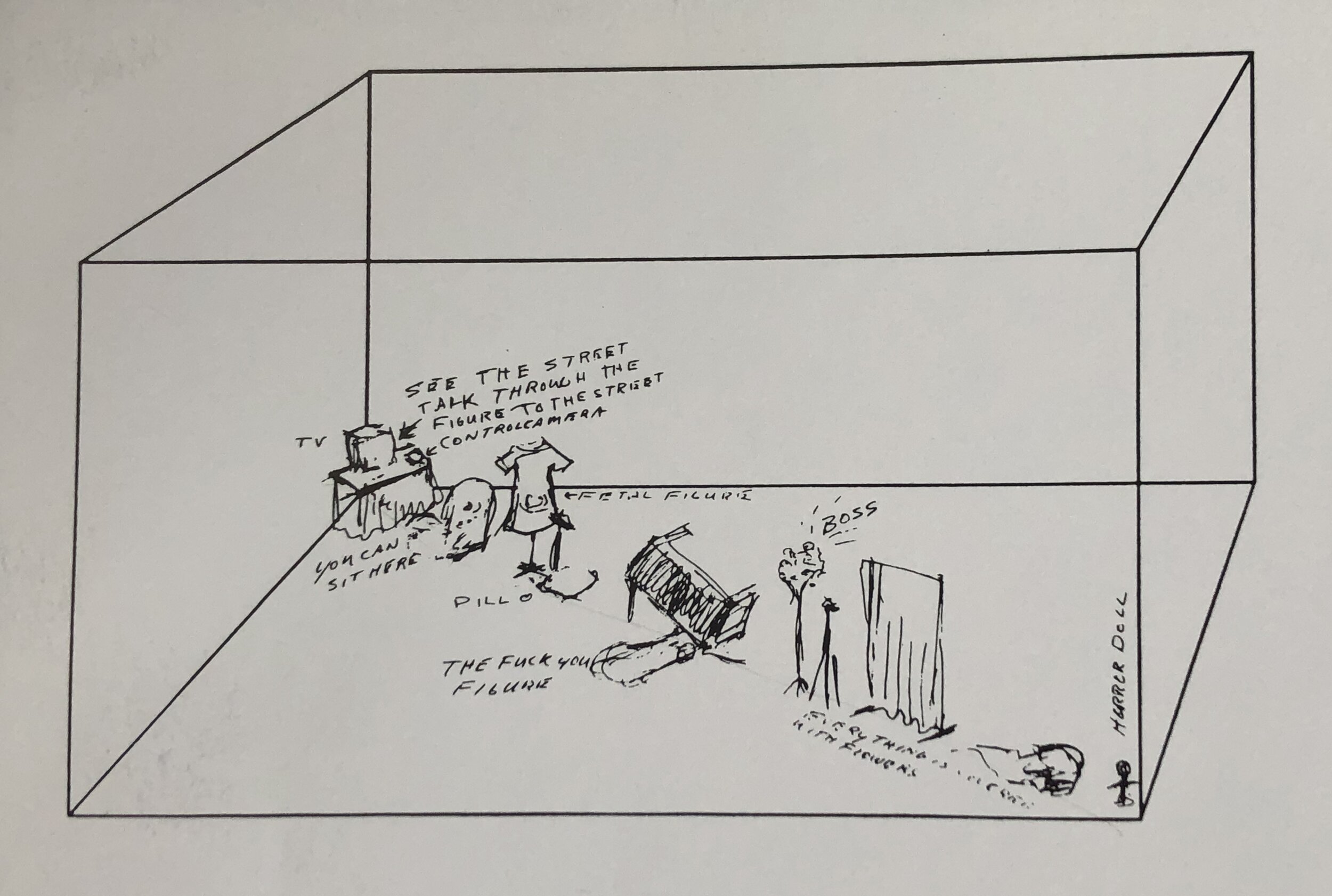

In Judy the protagonist is always positioned diagonally, bisecting the exhibition space and forming a schematic for the various facets of a multiple personality. Linguistically, the performances are based on testimonial and first-hand accounts of published abreaction cases. In line with the concept of the 'multiple', which often inhabits inanimate objects, aspects of the Judy character are not restricted to human form or scale. A unifying factor in this work is to be found in the clashing layers of floral patterns and soft domestic materials which become camouflage screens for the performers. Set out in a line, the installation begins with a "little" horror doll in a corner, followed by abstract lumps, a curtain, a bouquet of angry flowers, an upended couch sheltering a hiding figure, and a dress with a naked figure returning to the womb. It ends with an interactive section. Here the viewer is invited to sit in a comfortable armchair, to look and speak through a simulacrum and to operate a surveillance camera and sound system inside a dummy located on the exterior of the building; the effect is to draw the viewers' eyes and ears into a new perspective, and the work into the public sphere.