Magical Variations

July 22nd - August 7th, 2020

Online, Lehmann Maupin Gallery

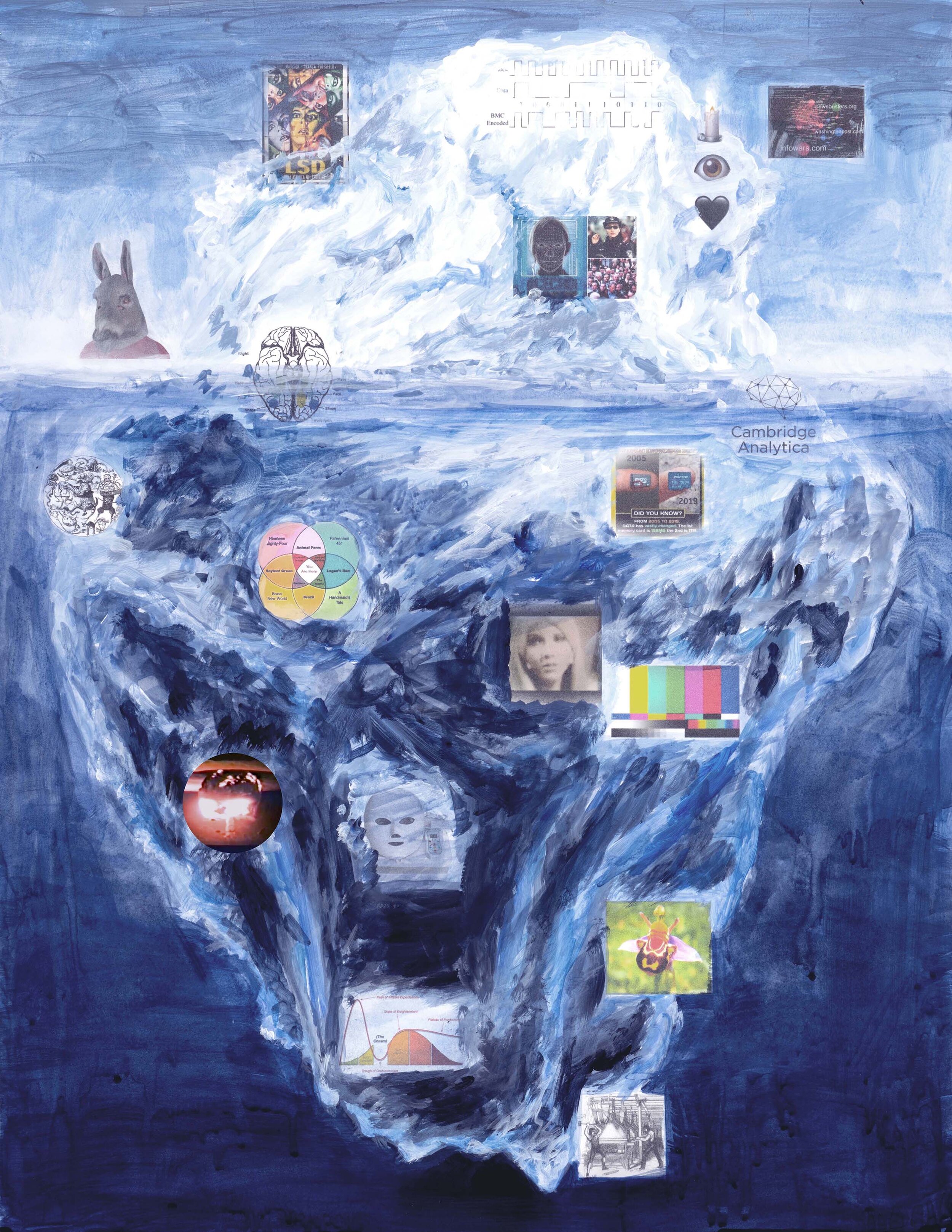

Magical Variations features nine new works by New York-based artist Tony Oursler that combine painting, drawing, printing, and collage with embedded video components. This series continues Oursler’s decades-long investigation into the lasting effect technology has on humanity and his exploration of the boundaries between technology, nature, and culture.

For the works in this presentation, Oursler employs the concept of magical thinking―the belief that one’s ideas, thoughts, actions, words, or use of symbols can influence events in the material world―to draw connections between technology, culture, and seemingly unrelated historical and apocryphal events. Using magical thinking as a lens, Oursler creates sophisticated narratives that ask us to question the veracity of information we have long taken at face value, provoking significant questions about both our future and our past, and challenging what defines truth and the role of technology in society today.

To learn more about Oursler’s interest in magical thinking, read his recent writing on the occasion of his 2019 exhibition Tony Oursler: Water Memory at Guild Hall in East Hampton.

Combining hand-made images with intricately layered videos, Oursler brings together disparate subjects such as the tale of the Headless Horseman and the 1969 Apollo 11 Moon landing, 5G conspiracies and the destruction of redundant iPhone models, and new age iconography and infrared footage from a shopping mall. Oursler merges these and countless other references to obscure histories, inviting us to observe how we learn, explore, and understand the complex narratives that shape our world.

“There’s so much magical thinking around technology. The idea is that you’re going to be taken care of by Google or Facebook, but you’re not being taken care of…in truth it might be the opposite.”

Tony Oursler

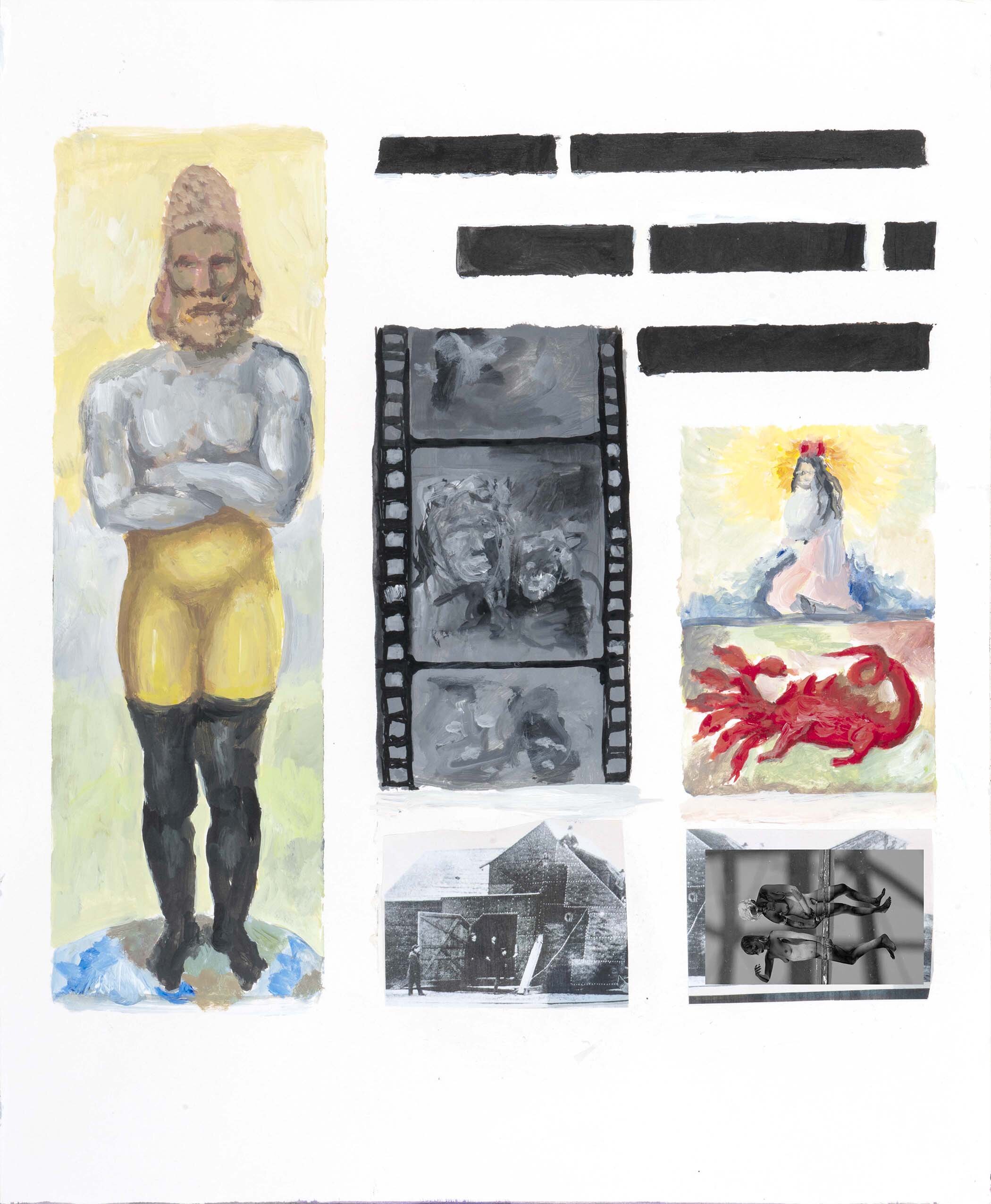

In Upsidedown., Oursler presents a literal representation of a contemporary luddite, layering image after image of human vs. technology. The figure featured on the left is Ned Ludd, the mythical leader of the Luddites, a secret oath-based organization of 19th century English textile workers who formed a radical faction that destroyed textile machinery as a form of protest against the early automation of labor. Ludd is surrounded by images of a cell tower on fire, five planet-like spheres, a hand-painted QR code, pixel lines, and a small circular video montage that portrays the modern technology most likely to be detested by a present day luddite.

In this video, broken and pixelated screens are smashed with sledgehammers and golf clubs, iPhone models are destroyed in a giant metal shredder, and images of QR codes reveal a series of 5G cell phone towers that were destroyed due to a social-media-spread erroneous theory related to Covid-19 and Bill Gates. The combination of these elements invites the viewer to contemplate the success and failure of the technologies we have come to rely on in our daily lives, and suggests that perhaps progress is not as glamorous as we assume

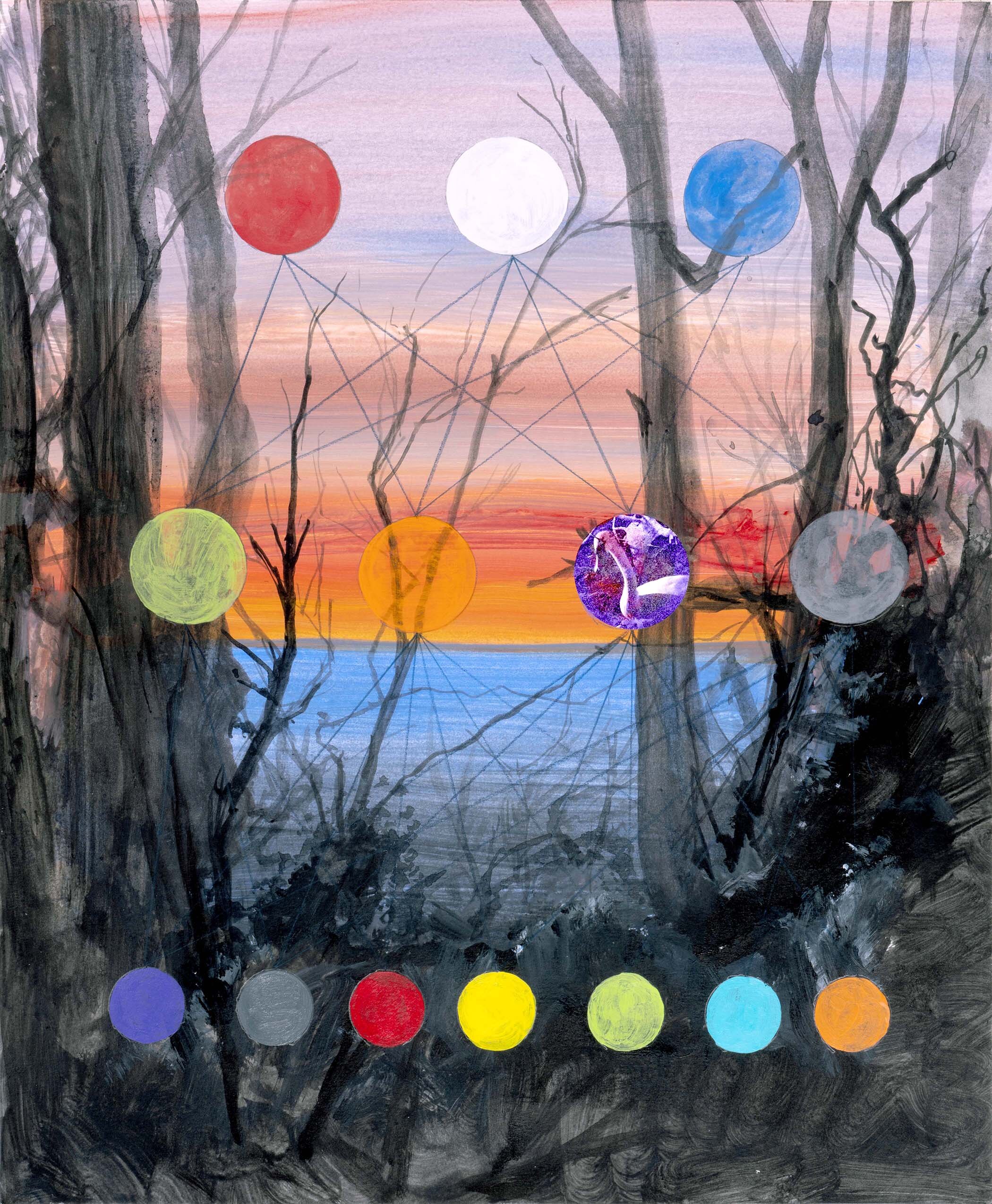

Headless. depicts the legendary Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow, shown brandishing a jack-o’-lantern and chasing a man on a white horse. This illustration refers to the tale of a Hessian trooper who was beheaded during the American Revolutionary War. Buried in a cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York, his ghost is said to rise every Halloween wielding a jack-o’-lantern as a surrogate head while he hunts for a permanent replacement.

The moon in Oursler’s rendition gives way to a video montage of both still and moving images referencing the 1969 Moon landing, the conspiracy theories surrounding its authenticity, and the tradition of carving pumpkins for Halloween. Like many works in Oursler’s oeuvre, Headless. invites viewers to imagine multiple readings of the past and present, in the slippery place between historical fact and fiction.

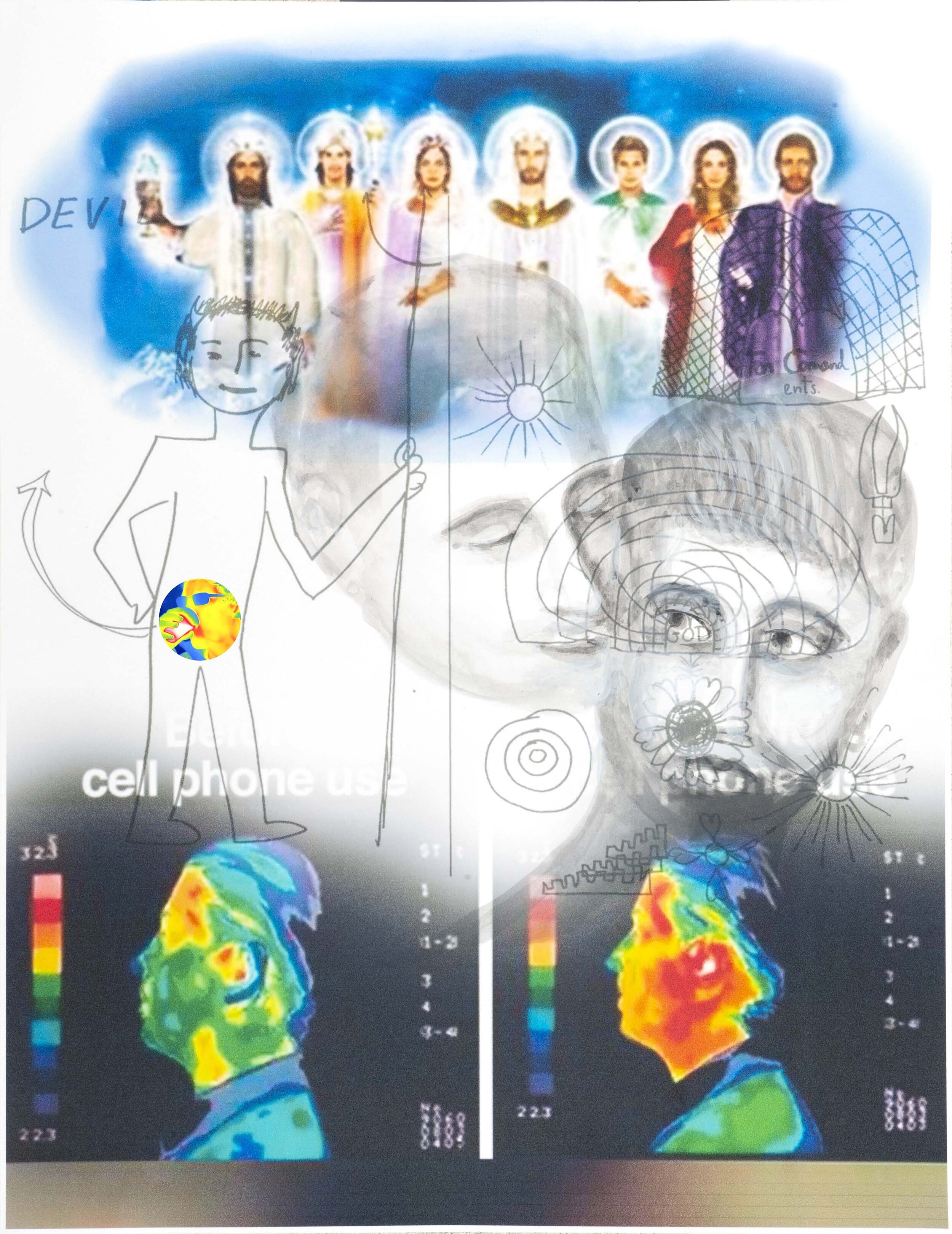

Oursler’s Remote View combines both traditional and non-traditional images of archetypal figures, including the Devil, angels, Jesus and his followers, and scenes from the apocalyptic Book of Revelation to explore the unstable dichotomy between good and evil. The title and images refer to the practice of remote viewing, in which extrasensory perception (ESP) was used by the pentagon during and after the Cold War to seek clandestine impressions about a distant or unseen subject. The artist points out that this practice, often associated with parapsychology, religious sects, and science fiction, was also practiced by the U.S. military and has developed alongside technological advances.

A small video montage features a male actor with devil horns dressed in a nightshirt and engaged in a trance, images of the solar system, animated religious illustrations, ancient Assyrian sculptures and reliefs, pseudo-informational videos of magnetic fields, and infrared footage of a mall, the subway, and Oursler’s own face. Oursler brings these elements together to illustrate various types of remote viewing, from the paranormal, to the spiritual, to that enabled by modern day technology―which gives everyone the ability to view remotely.

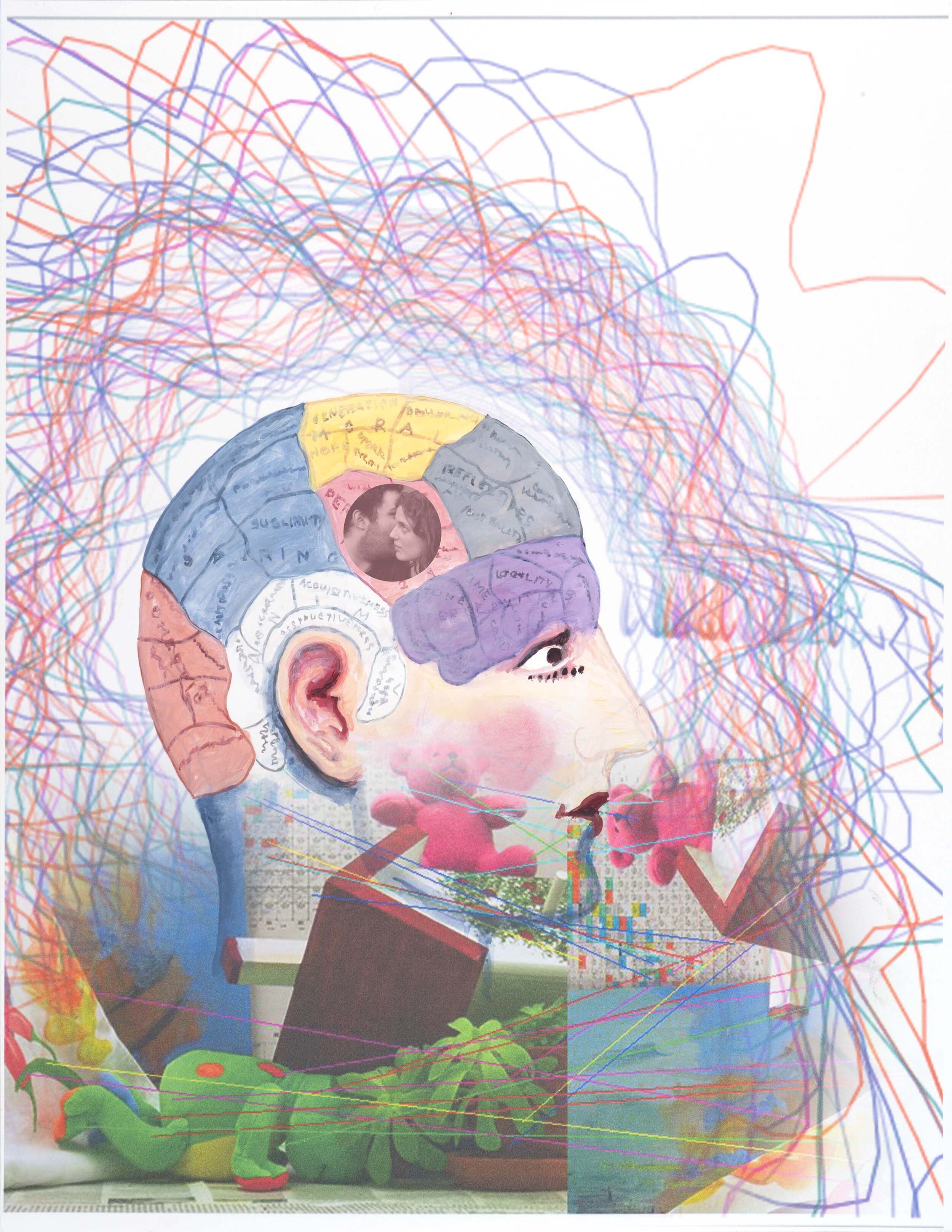

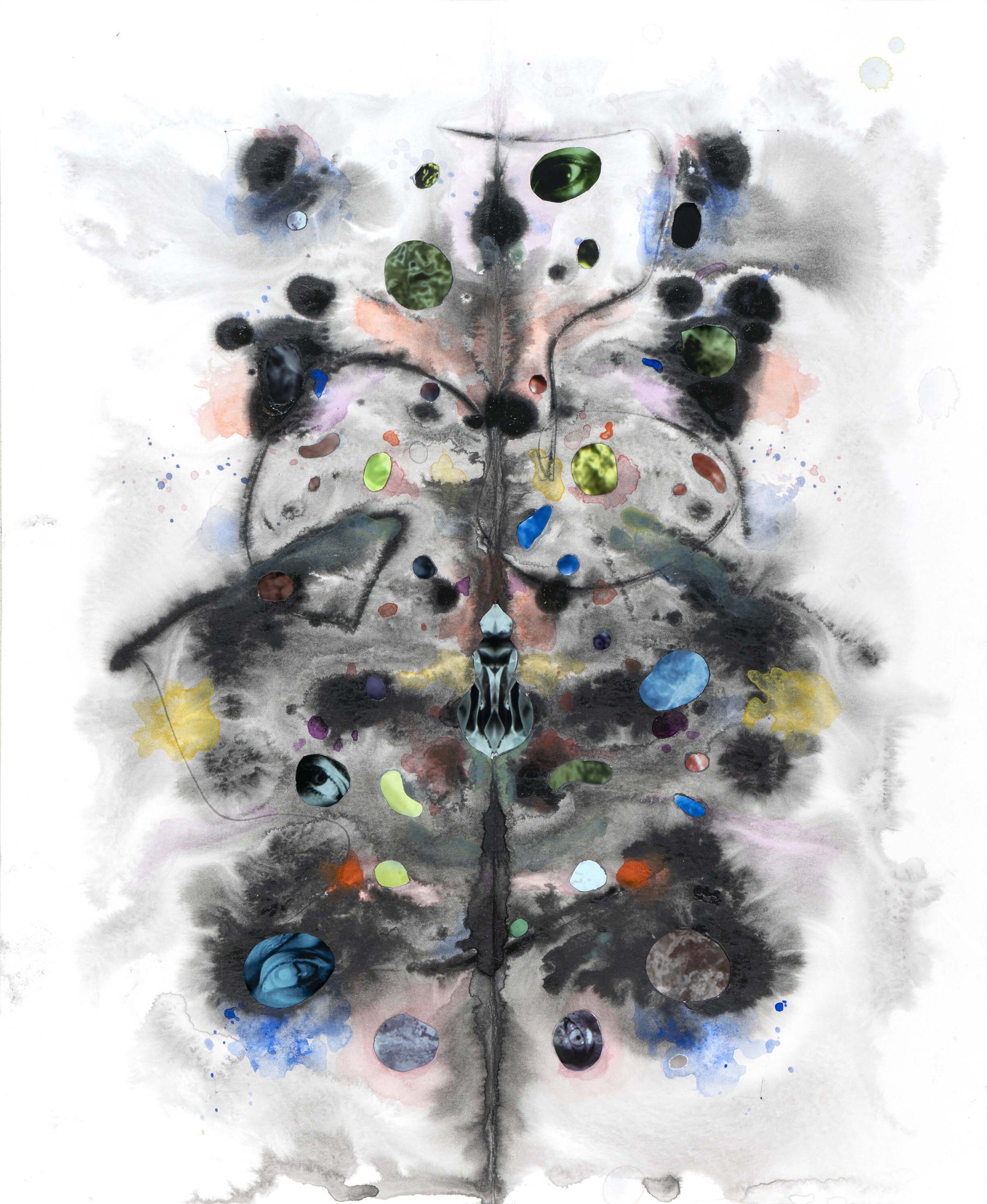

For Oursler, his Rorschach paintings and drawings are “the litmus test of humans," exposing the individuality of the human psyche that a machine, robot, or other form of A.I. would have difficulty predicting or replicating. The inkblot painting style is achieved by transferring paint from one panel onto another, creating a mirror-image that is nearly identical but bears marks (and imperfections) of the human hand.

Small videos featuring abstracted bodies, eyes, hands, and arms are interspersed throughout, the legibility of the body coming in and out of focus as the figures move and dance, themselves becoming a human Rorschach.