July 18, 2016

Tony Oursler

by Maika Pollack

"I'm a multimedia artist. If it’s not in the museums or history books, then where’s my art history?"

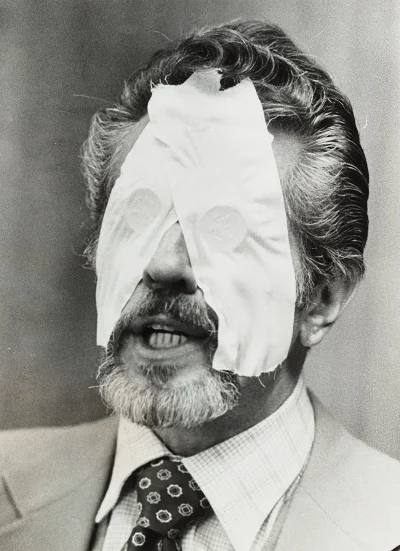

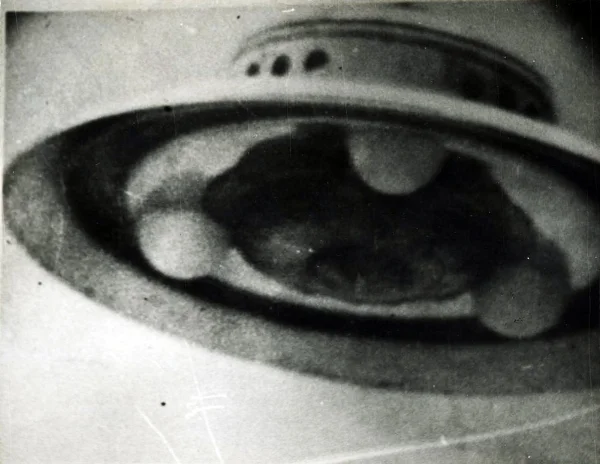

Dr. R. L. Noran, an ESP practitioner, with half-dollar coins taped over his eyes to prohibit the use of his visual sense during an ESP demonstration, ca. 1978. Courtesy of the artist's archive.

For the past three decades Tony Oursler has been known for his videos, installations, and public projections. But he is also a collector of images—mostly photographs, alongside books, posters, and other objects—which together map esoteric practices and collectives that range from 19th-century spiritualism to ufology and the Baader-Meinhof group. A show of works from this collection, Tony Oursler: The Imponderable Archive, will be on view at the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, through October 30, 2016. A feature-length, immersive 5-D film and large-scale installation, Tony Oursler: Imponderable, is now on view at the Museum of Modern Art through January 8, 2017.

Maika Pollack Why is your film called Imponderable? And why is the Bard show called The Imponderable Archive?

Tony Oursler Recently I became fascinated with early science, reading all these books and taking “The Great Courses” series. I kept coming upon this word imponderable—for example, when reading about Newton's idea that gravity was connected to the moon, that it moves the planets around. It was a major breakthrough, yet he couldn't figure out what the medium was, so he called it imponderable. He got the big picture, but he also knew where his knowledge ended. So the imponderable is a recognition of our limitations. It's an old term, but it doesn't go away. Today, the imponderable is always there in physics, and life in general—that mysterious place outside all our preconceptions. It's what's left when your worldview melts away.

MP: When did you start collecting the work that's in the Bard show?

TO: I'd say the earliest is probably from the '70s—a “Shroud of Turin” image. Back then, I would keep things that impressed me, like cult pamphlets or a National Inquirer image of a vampire kid or an alien.

In the '80s I saw an exhibition of Philo T. Farnsworth's hand-blown TV tubes, and I could barely resist stealing one out of the shell. The only reason I didn't—beside the fact that I haven't stolen anything since shoplifting as a kid—was out of respect for his collaborator and widow who was present and so proud of these things they made together. Also, there was this feeling that these objects belong to everyone. It's important for everyone to see that these machines were made by hand. I couldn't believe how powerful and resonant they were—almost organ-like. At the time, obviously, no one really cared about him, but I was drooling.

MP: But what would you do with it? Would you just take it home, put it on the table, and be like, "God, that’s amazing"?

TO: Yes, exactly! I'd say that over and over, and look at them for hours and hours. Trance out and think about the very first flickering pictures zapped through those tubes, what it meant for civilization or brain damage, or how much time was wasted staring into these tubes, or how that permanently changed the way we see. I still want one.

MP: How do you know when you want something?

TO: The want is always and endless, but it’s a bit foggy as to when it transitioned from vague wish to possession with intent. I think it was rare books that got me first. Then it was the things in those books.

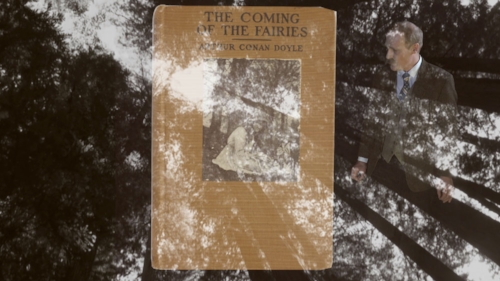

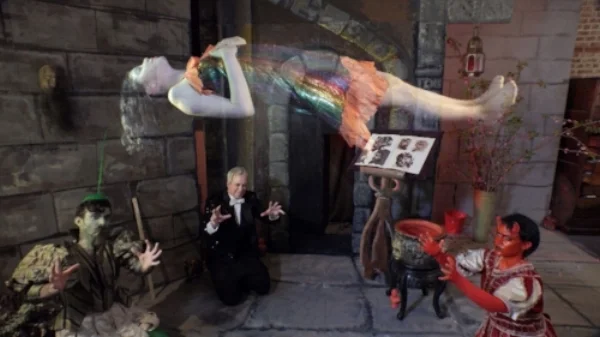

Tony Oursler. Still from Imponderable, 2015–16, 5-D multimedia installation. Courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

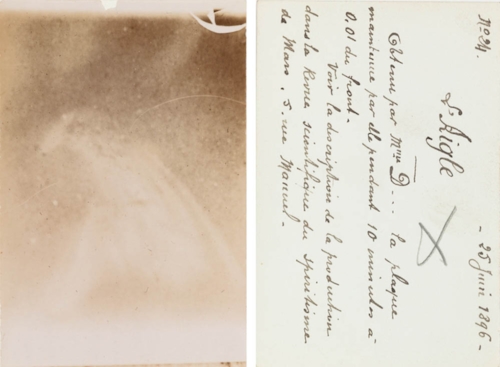

Research is big for me, especially since I have little or no education to speak of. So I dig around, and one thing I stumbled into was this: thought photographs. I was in Europe often and my friends at Pavot Gallery in Paris had some and explained just what they were. It blew my mind completely. Number one, I couldn’t believe that something like this existed and we didn't have it at MoMA. Number two, I thought it was the most poetic and interesting way of making an image.

Wait, do you know what a thought photograph is? In a nutshell, it's something that, I believe, was started by Commander Darget in France, sometime in the late 1800s. He was what we would now call a pseudoscientist, and also a photographer, and very interested in mysticism too. It was a time when science and mysticism overlapped and spread into all these pursuits and expanding social circles. Basically, he tried to capture thoughts onto photographic plates. He’d take a piece of paper or a negative and hold it up to the head, either thinking about something specific or not. Then he developed the image and, of course, there would be a haze of cloudy liquid blobs, which he would carefully inspect. And Darget also did this this wonderful thing—he wrote on the back of each photo describing what he thought it represented.

Thought photograph by Commander Louis Darget, with his notes penned on the verso, 1896. Courtesy of the artist's archive.

You also have to contextualize this, because around the same time was the invention of the x-ray and a new understanding of physics. Waves of energy that couldn’t be seen were everywhere. The x-ray allowed you to see the invisible via film, to look into the body. So that notion of seeing the unseen through photography, through technology, kind have spurred on this activity. Darget and others in my collection went on to record life forces, emotions, the soul, and dreams. When I found out about this I was overwhelmed with the poetics.

Anyway, they were also probably the first abstract photos. I can’t say the first abstract images, because I don’t know enough about that history, but they might be right up there with other abstractions.

In this spirit photograph, produced by William Mumler’s studio in Boston, the sitter is presented with a note: “Charity, To the brightest jewel in the crown, Nathaniel.” Courtesy of the artist's archive.

And Darget was not a trickster like the people doing spirit photos and things like that, though he knew some of them. He didn't doctor any of the negatives at all, and that's quite obvious when you see them, because they're real stretches of the imagination. Which brings us to, you know, what is that called in surrealism? When they used to rub the paper?

MP: Frottage.

TO: Ah, you speak French… So, it's kind of between Rorschach and frottage. A kind of pre-surrealistic practice of dream recording—saying nothing of the fact that it prefigured a lot of neuroimaging. Once, we might have said, “That’s ridiculous, you can’t record a thought!” But actually, today, you can. Pascal Rousseau wrote beautifully about Darget for our book, Imponderable. Part of this project was to commission text on part of the archive.

MP: When you started collecting this material, was it playing a role in your video work? Did you think of collecting as research for source material for your art practice, or was it more a separate project?

TO: At Bard there is a short film of mine, The Volcano, related to one Darget photo. But to go back: In the late ‘90s, I started thinking, I'm a multimedia artist. If it’s not in the museums or history books, then where’s my art history? I grew up on television, but I didn't know who invented television, or how that kind of inventive thinking shaped culture. I started thinking that was really strange, and that it would be a good idea to know more, so I started researching. Like Philo T. Farnsworth, maybe such people are as important to visual culture as painters? Looking around for that history caused me to make my own timeline. In a way, that works for the autodidact, the artist—a spatial graphic. In every city I found myself in, I’d go to the television museum or the communications museum, maybe the library. In my own half-assed way I started piecing this thing together, and of course it was before the Internet, so it wasn’t that easy.

Somehow I was like, I need to know about kabuki and early automatons—because there’s this rare print of a Japanese automaton from the 1600s. It was just the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen. I started to get exposed to the primary material. I got the bug for research.

MP: It's funny because, for most of us, we might really like something—like, say, a Philip K. Dick novel—maybe we even love it, but we wouldn’t necessarily go hunt down the first edition and collect it. What is it about the singularity of the original that attracts you, particularly as someone who works in multiples, video projection, and virtual images?

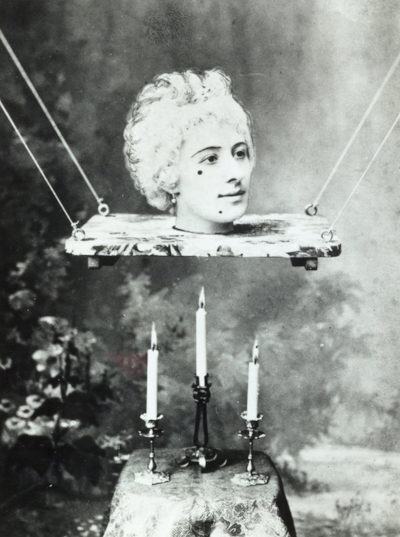

Production still featuring Jehanne d'Alcy, actress and wife of Georges Méliès in his film La source enchantée, circa 1890. Courtesy of the artist's archive.

TO: A lot of what I have is multiple, vernacular, or copied in one way or another, yet they may still be rare—not due to monetary value, probably more due to obscurity. In 1985, I met George Méliès’s granddaughter in Paris, and actually joined the Méliès fan club. At that time, there was only one slim volume published on his work. Now, I’ve worked with Jim Steinmeyer to write on his connections to stage magic and film. Such an important artist and completely ignored! I used to haunt the old film museum on the Trocadéro and look at the props he made, along with the Nosferatu sets.

Then, it was okay to lust from afar, and I collected images via my camera and photocopies. But the ‘90s, on our timeline of mimetic technologies, was a jumping off point. The closer I got to the real thing, the closer I felt to the social systems connected to them. I guess the real object, like ectoplasm, helped me understand, or baffled me completely, with regard to veracity.

MP: So they have a life in your life after being collected?

TO: I’ve had people tell me that it's actually elitist to have the original. But that's just the opposite of what I want. These collections are connectors, for better or worse. They tell a story. I mean, I don't really want to be connected to the Manson family, but actually I did camp out with a group of them once, believe it or not. When you see a drawing by him it reveals something. Another thing is this: that original Philip K. Dick book you mentioned? It looks much better than the later editions.

Mumler spirit photographs pasted into a family scrapbook. Courtesy of the artist's archive.

MP: (laughter) What’s an item that’s really important to you?

TO: Well, there’s this vintage scrapbook, all in memoriam of a family—like a death album. It had seven images by William Mumler, who was the first spirit photographer, so it's actually a scrapbook from his time. But it also has a big piece of mica glued into it, floral things, and more ordinary scrapbook stuff. To have that context is mind-blowing, as usually these pictures float around in a great sea of old images. But this is where somebody would keep spirit photos—mixed in with family photos as a sort of proof of an afterlife.

Then there’s this 38-volume set called the Spencer Collection, which seems unreal. Each is hand-written in Latin and old Italian. When I first acquired it, almost by a fluke, it was hard to tell what it was. For Imponderable, we hired someone to research it. Now we think it was made in Milan in the mid-1800s, as part of a cult recipe book with basically every form of cult practice, from geomancy to necromancy, devil summoning to spell casting, angel communicating to stuff I had no idea existed. The spooky thing is that the books were most certainly for active practice. One chapter is "How to make a homunculus.” I think I almost cried the day we discovered that section!

MP: Did you try any homunculus-making?

Tony Oursler. Still from Imponderable, 2015–16, 5-D multimedia installation. Courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

TO: I've been doing video dolls for years, but they're not spirit-controlled entities. But no! I don't try any of that stuff. I'm horrified. Maika, I don't want to pierce the veil… to the other dimension.

MP: So if you aren’t using them, what is your fascination with these objects?

TO: You know, my fascination with these objects is how they open up onto belief systems and worldviews. Therein lies the beauty. This is the scaffolding of a lot of my projects.

But another of my favorites is a set of photos Howard Menger took while aboard an alien craft that took him to the moon. You start to get the morphology of all these UFO things, the culture behind it, books published, conventions, and how life becomes so exciting for these believers.

Photograph of an unidentified flying object taken in 1952 by George Adamski, a prolific American photographer of UFOs. Adamski claimed to have several encounters with aliens beginning in the late '40s, and even stated that he had been taken aboard alien spacecrafts and traveled to different planets. His claims drew the attention of several skeptics, and after a series of investigations, his photographs were eventually discredited. Courtesy of the artist's archive.

MP: UFO photos, 18th-century magic show posters—I opened up your closet where you keep the archive and the categories were mind-blowingly eccentric when seen in proximity. What kind of work is a collection? What information does it produce?

TO: The actual source material is meant to be read differently by everyone. I tried to keep it that way in the book, too—like a landscape of shifting beliefs. The information and patterns to be gleaned from the archive change for me. At some point I wanted to look at technology: rational versus mystical. At other times I wanted to curate a show related to cults and follow patterns, but that lead to depressing facts about abuse. One thing it’s done is help me to ask: What is the current, agreed upon reality here in America? If you bother to scratch the surface, it turns out that high percentages of people believe in ESP, UFOs, ghosts, and one in three does not believe in evolution. These are important things to know about reality now.

MP: It seems like a lot of the themes in the book challenge the role vision plays in our sense of knowing anything by measuring or representing the invisible. Magnetism, Mesmerism, LSD, fairies, Kirlian photos, aliens. And I was thinking about how the curator Pascal Rousseau writes about those blobs in double exposures. He calls it “fauxtography,” like these photographic mistakes. Does the medium itself help us see something, and what’s the role of media is in the collection?

TO: There's a tracing of the way technology forms an image, and these images always reflect our desires and needs. And there's even a book, Spectropia, 1864, based on after-images. You're meant to look at images in the book, then look away and see after-images floating in the room. We’ve always wanted to go into the dark to watch the shadows—in that sense, the medium tells us much about ourselves. Phantasmagoria is very hard to collect, but that kind of pre-electronic image production fuses performance, optics, light, and architecture in all these fascinating ways. I think it will eventually be seen as a super important part of our history, though there's not much evidence because it's all ephemeral.

The True History of Pepper’s Ghost by John Henry Pepper, 1890. Courtesy of the artist's archive.

There are mechanical depictions, like schematics—because you can't explain, say, a Pepper's ghost in a book. Noam Elcott is one of the few who could contribute on this important history for the Imponderable book.

Another forgotten character appears in both the book and the film—Robert Williams Wood, this guy who invented the blacklight. He was also kind of an important debunker and a poet, inventing all sorts of sonography. He had a keen visual sense, and much of what he discovered was due to his fascination with optics. He has a crater on the moon named after him. To me, this particular guy was responsible for certain psychedelic stuff that came later in culture. It’s fascinating how scientific phenomena become cultural phenomena.

I'll mention one other guy—William Crookes. He invented the cathode ray tube, which had a double purpose: x-ray and television. That’s so poetic. He was a sort of pre-physics guy but then he ends up wonderfully derailed by, I believe, a young spirit medium named Katie King. She ends up in his laboratory and convinces him that she can turn into a spirit. So, he designs some psychic experimentation. The guy who basically invented x-ray and television also made fantastical devices to weigh spirits and generate random language from spirits.

MP: In his show about telepathy [“Cosa Mentale: Les imaginaires de la télépathie dans l’art du XXe siècle” at the Centre Pompidou], Pascal Rousseau describes some late-19th-century material as attempts to make visible the human mind and its capacity to reach out into space and transmit information electromagnetically. He writes about the 19th century as marked by the development of industrial telecommunications that transform our relationship with time and space. So, belief in mental forces like empathy, telepathy, and ether develop alongside technologies like x-rays, wireless communication, or radio. He sees this as the start of networked communications between people today—kind of externalizing the functions of the mind.

TO: Right, I love Pascal’s take on that—it's so insightful. The externalized brain is key.

The Internet itself is like one big mirror of the collective mind. You know, I kind of came at this a few years back, thinking about the uncanny valley for an Internet project with Tom [Eccles]. There’s this Japanese roboticist by the name of [Masahiro] Mori who came up with the notion of the uncanny valley. In the ‘60s, he talked about robots approaching what will be indistinguishable from human forms. And right before they really approach our likeness, they cause a repulsion, a rupture in our consciousness, which would be the uncanny part of it. People always use Tom Hanks in the movie Polar Express as an example. He’s so horrifying in there, because he’s kind of real but he’s not, just rendered. I thought to take this a step further—it’s not going to be a mirror of a person, or a visage. It’s going to be a mirror of the mind that will become slowly more uncanny.

Where is that happening? It’s clearly happening on the Internet, like this big data aggregation. Facial recognition is a big part of it and, believe me, the computer does not care about visually imitating us. It's the information that counts. Why are we the way we are? That’s all in the numbers. Funny, the Internet almost looks like an old phrenology chart of the brain. Like, here’s the mathematics part, and here’s the photo part; here’s the language part, and there are all the books, then here’s the sex part; and here’s the bodily function part, and so on. It’s all just being catalogued right now, and soon we’re going to have a perfect model of consciousness. Or, not a perfect model, but an average, a total model, because everything will be in there. In that sense, you can trace that back to stuff like television and right back to the telegraphs. Each one of those strands took care of a different facet of humanity in some way. But I see it as a big progression, ending with the Internet—the end game.

Tony Oursler. Still from Imponderable, 2015–16, 5-D multimedia installation. Courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

MP: It’s exciting that your film, Imponderable, is being shown at MoMA. I was thinking about a friend, Charles Bernstein, who was pretty irate that MoMA's Inventing Abstraction show, in his view, silenced a history of abstraction that he felt was much less pure than MoMA was presenting in that particular exhibition and much more invested in the spiritual and in the proto-psychological. And I'm excited to see your show taking place in that institution, maybe because your work opens up and investigates histories of the origins of abstraction that have been, if not suppressed (that’s too strong a term) maybe not given great emphasis in the way we present abstract art in America.

TO: I’ve thought a lot about that because the whole impulse of art history, at least now, is to kind of strip it of its cultural context when, for better or worse, the motivations of all the producers are what's interesting to me. And I think the question is: Does it matter? It does if you want to prove a point, and it doesn't if you want to set the art free. Can you strip away Kandinsky from the books that he wrote?

MP: Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

TO: Yes, Maika, are you a computer? You know everything. (laughter) Yeah, and also the ones that describe the different zones of abstraction and give them some kind of meaning, like, "This is home," "This is an emotion." He made up these fantastical systems—and here we're gonna take our cultural baggage from this moment, which in this crossroads is very, what's the word? Atheistic?

MP: In France they say laïcité. It's this separation of church and state on a fundamental level. Sometimes I feel like that about art history, too.

TO: It’s just that dogmatic in the artworld—because what's her name, the new one that everyone is looking at, the Swedish woman…

MP: Hilma af Klint.

TO: It's a big issue because she precedes other abstract people, but they sometimes undermine her, saying she was illustrating a spiritualist belief and thus not an abstract painter. But that’s utterly ridiculous, because Kandinsky was a kind of spiritualist. Plus, to me, it's just beside the point.

That's why thought photos, because they're connected to neuroscience as much as to the occult, will take a long time to get assimilated into the canon. I don't really care. I don't think people have to be ashamed of the fact that someone was tricked into making a fantastic image through what might be a strange belief system. And you can also say that a lot of the art systems we grew up around, even conceptual art or minimalism, could be just as strange a belief. The tenants of Donald Judd might be as weird as Christ on the cross in a thousand years.

Maika Pollack recently completed a PhD dissertation, “Odilon Redon: The Color of the Unconscious” at Princeton University. She is a visiting professor of art history at Sarah Lawrence College, and a writer and gallerist in New York City.