Tony Oursler’s Ghost Stories

By Sarah Trigg

Tony Oursler in his studio. Photo: Sarah Trigg

Tony Oursler’s never been afraid of the creepy, so maybe it shouldn’t be surprising that when I arrived at his Lower East Side studio, the room was dark, and props from a film shoot — skeletons, witches brooms, animatronics, and blown-up spirit photos from the 19th century — lurked around dutifully awaiting their cue. Blocking even more sunlight was a contraption that Oursler invented to project his forthcoming video four-dimensionally, using mirrors. Maybe it’s even less of a surprise that Oursler’s grandfather was a magician interested in séances and popular mysticism.

Oursler made his art historical mark in the '70s and '80s with his single-channel videotapes and installations, and later in the '90s with video projections of disembodied facial features onto pillowed forms and sculptural surfaces (even smoke!). Amusing yet perturbed, these characters often speak in poetic, cryptic language and appear trapped in the ether between humanity and technology. They are apparitions of sorts.

We spoke about his current exhibition at Lehmann Maupin and his upcoming film and book.

Works from Oursler’s exhibition at Lehmann Maupin. Photo: TONY OURSLER EUC, TONY OURSLER CV(15), TONY OURSLER INK, TONY OURSLER OWE; 2015 wood, LCD screens, inkjet print, sound performed by Holly Stanton, Jim Fletcher, and Brandon Olson 113 x 71.5 x 30.5 inches (with base) 287 x 181.6 x 774.7 cm Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

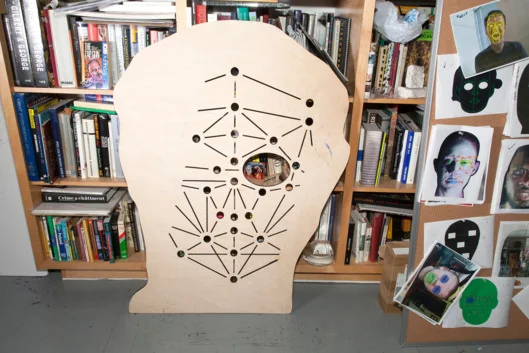

“I started thinking these pieces are the way that machines are looking back at us,” said Oursler. “A couple of years ago I was on the internet and came across what is known as Eigenfaces, which are an extension of this facial-recognition photography indexing the face. For my very first videotapes, I did some variations of those flip books with different sets of eyes, noses, and mouth. So I’ve been interested in this idea of identity through face, collaging, and the way that works with media for a long, long time.”

The geometric patterning on the faces of Oursler’s new works relate to the algorithmic points in facial recognition technology used by banks, governments, law enforcement, and, of course, Facebook. “To set pattern recognition, you need set points — pupil width, cranium size, things that don’t change over time. For me, it’s a metaphor for what’s happening now with big data and a tectonic shift in identity and portraiture. All this material is now instantly accessible via these databases and becomes linked — your Google searches, bank history, history of crime, financial information, education, spending patterns, transportation patterns, medical history, DNA, even odor and pheromones. Portraiture today is no longer a chiaroscuro painting or photographic mugshot. It’s about this swarm of invisible data. It’s changed the way we think about ourselves, and that’s what I’m trying to bring up with the exhibition.”

A template of facial recognition points and documentation for Oursler’s current exhibition. Photo: Sarah Trigg

In a whisper voice, each face in Oursler’s exhibition delivers their internal contemplations (written by Oursler) concerning our privacy, sharing of information, and identity. Oursler found algorithmic face recognition patterns on the internet, which he then superimposed on to faces of individuals he had videotaped in ultrahigh definition. “I started out with the Eigenfaces, which are ghost-looking, but then I became really attracted to this hard edge — this sort of graffiti tag or high-tech mask structure.”

Oursler says he’s noticed the variation of these algorithmic patterns (which are available on the internet) grow exponentially within the past year. But what about the more abstract, chaotic ones? “I love those because they’re very frenetic, like shotgun blasts. But to me what’s interesting is that this machine is really looking back at us. There’s this ceding of authority to these algorithms, machines, and structures. They’re not really controlled by us at a certain point. In this body of work, I wanted to get the tension between these surface mathematics and the character, this spark of life, that everybody has and that will never be able to be captured by any machine. I wanted to really emphasize the individual breath of a person.”

During our visit, however, another project was on the front burners of Oursler’s attention. A few years ago, Oursler embarked on archiving into book form his massive collection of ephemera and collected objects relating to the invention of the camera obscura up to the present and the many belief systems that shifted or were born in response to our narrative, emotional, and spiritual grappling with this technology. Oursler’s extensive research has been the primary source of inspiration for his art practice.

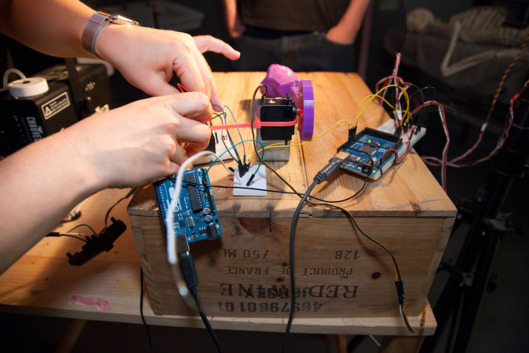

A set of robotics undergoing testing for the film. Photo: Sarah Trig

Many projects have come from Oursler’s timeline and archiving project, including numerous installations, web projects, and texts. Currently, Oursler has returned to single channel video-making, which was once at the foundation of his practice. While preparing his book project with the curators Tom Eccles and Beatrix of Maja Hoffman’s LUMA Foundation who have been working with Oursler on a related project in Arles, France, Oursler decided to synopsize part of the archive into a film, which at its core tells a family story.

“My grandfather, Fulton Oursler, was a poor guy, grew up in Baltimore, auto-didact. His aunt and mother took him to many séances when he was a kid. He basically kind of grew up under the séance table. That led him to be interested in magic because he noticed the tricks happening in the séance rooms. By 16, he was doing magic himself and he was very skeptical of séances. He was also a writer. He moved to New York and works with the Macfadden publications here. True crime, true detective, and many other things ... He befriended many famous magicians ... Houdini, but others too. He writes a play called The Spider, a Broadway hit involving a magic theme and breaking the fourth wall in the theater, which was pretty radical in the '20s. In the play, during a mind reading, an audience member is shot as if something is being exposed that someone didn’t want revealed. They seal up the theater, police come in. This is the play. You’re locked in and they have to solve the mystery. He’s also exposing mediums and séances.”

Grandfather Oursler, as well as Houdini, sought to debunk Spiritualists common in their day — particularly those defrauding widows desperately trying to connect with dead relatives, post World War I. One of the mystically oriented, strangely enough, was the creator of the ultrarationalist literary character Sherlock Holmes — Sir Arthur Conan Doyle — who claimed to “verify” spirit photography of ghosts, ectoplasm, and mystical creatures such as the Cottingley fairies. Oursler’s grandfather actively corresponded with the author and, despite his utmost admiration of the writer, he exposed him as a fake by sending him double exposure photographs — which Conan Doyle had authorized as official documentation of the spirit world. “Their correspondence is basically one small part of perhaps eight objects in my collection. I’m thinking of this being a series of films, which would branch out from other elements — interests in cinema, UFO photography, the occult, stage magic, cults, religious cults, mesmerism, sorcery, voodoo, religious artifacts, apparitions, pareidolia, pseudo science that connects to cults, and the various belief systems — the list goes on and on.”

Oursler’s book, out July 5, includes around 1,500 images of his archive along with a collection of essays. Partway through the project, Oursler decided to create a narrative film. “I started to look at the whole archive as a kind of index of belief systems. A record of these conflicting and connecting belief systems ,which in a weird way is what my work is about. In the film, I go back to this core story — the spirit photos, the séances, the spiritualism versus magicians versus mystics, and how stage magicians come out of that and become entertainers. There’s a connection to psychotherapy, which was a nascent thing then and connected to psychic research. There’s also a political aspect — women didn’t have the vote yet in the 1920s. Emancipation and feminism were important aspects to the mediums at the time. Women were able to have this position of authority, which they gave themselves. Not all these mediums were bad in any way. Mystics like Margery Crandon (whom I absolutely fell in love with) were self-expressive surrealists. They generated images, performance, random stream-of-consciousness texts. They used lights and props and sound. Surrealists like Man Ray were obviously looking at this type of work. Crandon didn’t derive money from her medium-ship, so she was outside of the financial fraud."

Oursler explained that two female poles anchor the story — Crandon and his grandmother. “My grandmother was a woman of agency. A very activated and liberated person. She wrote books, movies. Numerous films were made from her books, such as Night Nurse. Whereas Marjory’s stories had almost a folk aspect. She gained a lot of notoriety by generating conflict, so she’s tested all the time. Houdini tests her. Conan Doyle tests her and believes her. Various scientists test her. They called her the Witch of Beacon Hill. Houdini built this box to test her in, which wasn’t too far from Salem. That’s why there’s a kind of witch element.”

Oursler’s exhibition at Lehmann Maupin runs until June 14, 2015. His film and book project will launch in Arles, France, and will travel.

Sarah Trigg is the author and photographer of STUDIO LIFE: Rituals, Collections, Tools and Observations on the Artistic Process.