Tony Oursler’s Grand Illusions, Science Left at the Door

A Tibetan kapala skull from the 19th century that would have been used in both Hindu and Buddhist tantra rituals, at the exhibition “Tony Oursler: The Imponderable Archive” at the Hessel Museum of Art at the Bard Center for Curatorial Studies. CreditByron Smith for The New York Times

In Paris in the early 1780s, Franz Anton Mesmer was attracting attention for his showy demonstrations of “mesmerism,” or what would later be called hypnotism. King Louis XVI appointed a commission that included Benjamin Franklin, America’s ambassador to France, to investigate.

The commissioners’ report debunked Mesmer’s theory of “animal magnetism” and proffered comments — widely attributed to Franklin — on the attractions of erroneous beliefs. “Truth,” averred the writer, “is uniform and narrow,” but in the field of error, “the soul has room enough to expand herself, to display all her boundless faculties and all her beautiful and interesting extravagancies.”

A scrying ball used by magicians and archival photographs featuring the magician Wilfred Sellten, left, and Harry Houdini. CreditByron Smith for The New York Times

The observation is aptly quoted in the doorstop of a catalog for “Tony Oursler: The Imponderable Archive,” a fascinating and amusing exhibition at the Hessel Museum of Art at the Bard Center for Curatorial Studies.

The exhibition consists of 680 items from a collection of more than 2,500 artifacts dating back to the 18th century having to do with scientifically unsupportable beliefs. Compiled by the artist Tony Oursler, it includes photographs, paintings, drawings, manuscripts, books, pamphlets and mechanical devices. There are publications and objects items pertaining to Satan worshipers, flat-earthers, witches, magicians, alchemists, mesmerizers, Theosophists, spirit photographers and other imaginative and often fraudulent cosmologists, lunder glass on 35 tables.

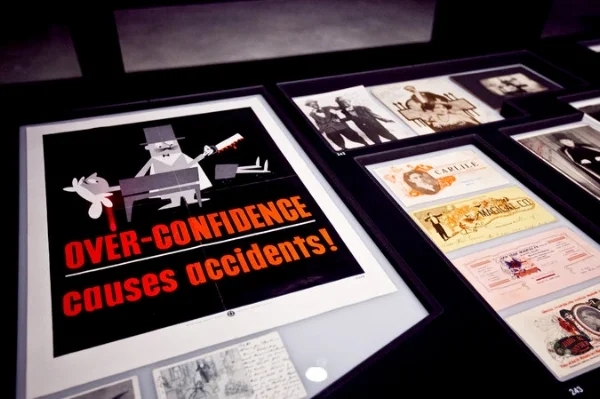

A 1920s German poster advertising stage magic, publicity photos for magicians (1910-1970s), and magician letterheads from the late 19th-early 20th century, are among the archival displays on the show.CreditByron Smith for The New York Times

Mr. Oursler’s archive naturally brings to mind the collections of Jim Shaw that were exhibited at the New Museum last year. But whereas Mr. Shaw looks to amateur paintings and kitschy religious artifacts with the eye of a connoisseur, Mr. Oursler is less discriminating about visual or poetic qualities. His archive feels driven more by a philosophical preoccupation with relations between illusion and reality. The overall effect is like that of a giant Surrealistic collage, a crazy quilt of superstition, paranoia, perversity and idiocy. It’s great fun to peruse.

One table displays photographs and ephemera pertaining to the career of a man named Charles Fulton Oursler (1893-1952), who was Tony Oursler’s grandfather. An amateur magician and successful editor, author and Hollywood screenplay writer, Fulton Oursler, as he was known, was a prominent debunker of the spiritualist-séance fad that arose in the 1920s. In the 1940s, after recovery from alcoholism thanks to Alcoholics Anonymous, he became a deeply religious Roman Catholic and wrote “The Greatest Story Every Told,” a best-selling life of Jesus.

“Le Volcan,” a video installation by Tony Oursler. CreditByron Smith for The New York Times

Fulton Oursler’s son — Tony’s father — Charles Fulton Oursler II, carried on the family legacy. He began as an editor at Reader’s Digest and then became editor in chief of the Christian magazine Guideposts. In that capacity, he founded a spinoff called Angels on Earth, which presents stories about intervention in human affairs by divine beings. Issues of the magazine are included in the exhibition.

Sequined baby voodoo doll from late 20th century. CreditByron Smith for The New York Times

Tony, whose full name is Charles Fulton Oursler III, seems to have kept up the family business. In the 1990s, he became known for sculpturesinvolving comically distorted faces and bodies of people projected onto stuffed dummies. Quietly mumbling and complaining, these figures were magically lifelike. At the same time, an obvious artifice created tension between the illusory and the real. The sculptures debunked themselves.

Unlike those of his religiously observant predecessors, Mr. Oursler’s beliefs are hard to pin down. As an archivist, he acts like an anthropologist presenting his discoveries without evaluative comment. Different tables are devoted to topics like Scientology, U.F.O.s, mind-altering drugs and thought photographs supposedly made by projecting mental ideas or images onto film.

The archive abounds in amusing surprises. On one table is a set of delightful colored-pencil cartoon drawings made by the director Federico Fellini from 1960 to 1990, including caricatures of Laurel and Hardy and a picture of a tiger in a room with similar pictures of tigers hanging on the walls. It’s eminently appropriate that the exhibition is presented on a college campus, as it should serve as an excellent study collection for students from a variety of disciplines including psychology, philosophy and art history.

Accompanying the archive in the museum galleries are two of Mr. Oursler’s recent video installations. Each video is projected inside a large, black box with a wide window allowing viewers to watch from outside. “Le Volcan” involves staged comical scenes with people in fanciful costumes acting out magic ceremonies and séances. In “My Saturnian Lover(s),” a woman and a boy eagerly await the U.F.O. she believes is coming to take them away. In both presentations, a strange three-dimensional quality is created apparently by double exposure. Looking inside the box you see that this is accomplished by rear-projecting one video onto a screen and projecting another onto a mirror on the floor in front of the screen, which in turn projects the imagery onto the screen.

At the Museum of Modern Art, a similar but much larger projection system has been built for Mr. Oursler’s 90-minute film, “Imponderable,” in which episodes from the history of spiritualist frauds and hoaxes are re-enacted while mystic flames, smoke and ectoplasmic phenomena come and go. At certain moments during the film’s progress, you feel breezes wafting over you and hear loud thumping under the theater’s risers.

The crudeness of these effects is part of the generally comical spirit. But Mr. Oursler is making a larger point about the confusion between illusion and reality to which human beings seem to be congenitally susceptible. As Franklin’s group pointed out long ago, truth is often hard and boringly consistent. For most people, fantasies and myths are more compelling and easier to comprehend, especially if they are conveyed by charismatic charlatans and demagogues using deceptive technologies.

Unlike his father and grandfather, Mr. Oursler is not a crusader for any particular belief system. He’s a secularist skeptic who entertainingly urges a circumspect view of any and all simple solutions to the mysteries of the universe. In these epistemologically perplexing times, that’s a valuable service.